How to Write While Avoiding Writing

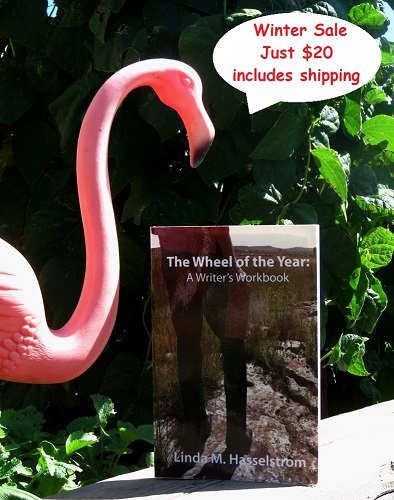

This essay appears in my book The Wheel of the Year: A Writer’s Workbook (2017). I posted this book excerpt on my blog in 2020, but am posting again with an update about the book at the end of this piece.

Today’s the day, I promised myself this morning, just as I did yesterday and the day before.

Yes, today’s the day I write an essay about Lammas for my business website Home Page.

Lammas is often marked by rituals emphasizing endings, as well as with the collection and preservation of food. How could I connect this season with writing?

Yesterday, while not coming up with any ideas for the Lammas message, I ambled through the garden mumbling curses on the grasshoppers and admiring the orange blush on a few green pumpkins. I investigated a water stain in the house where I conduct retreats, and filed some papers there.

Then, in a truly desperate avoidance maneuver, I moved my refrigerator out of its niche and cleaned under it before vacuuming its coils and washing spots off the door.

I was still trying to think of what to write for Lammas while I scrubbed the kitchen floor, vacuumed and dusted the house, and hung rugs and bedding on the deck railing to air. After lunch I finished up the plans for a workshop I’m giving tomorrow, including making a decision about what to wear. None of those activities produced an idea for my Lammas home page essay.

By 9 a.m. today, I’d read 50 pages of a mystery novel with my morning coffee after writing a few thoughts– not about Lammas– in my journal. After breakfast I tidied up the kitchen.

The day I originally wrote this Lammas essay, I played a game of Quiddler with my husband. We walked the dogs and then I planted some wildflower seeds, bathed the dogs while deciding what to fix for lunch and chopping vegetables to get started. I cleaned the washer, dryer and utility sink inside and out before I dusted and scrubbed the basement bathroom. I hadn’t done either of those things for months.

Most of my housework gets done while I’m avoiding writing.

I love writing; it has provided some of my greatest joys– in that moment when I’ve finally shuffled the words enough to find the perfect phrase.

But it’s also inspired hours of house-cleaning and staring into space, activities suited to trying to think what words need to come next. So, my subconscious and sneaky brain can find all kinds of logical ways to avoid it.

Finally, I sat down at the computer– and immediately decided I needed to change the location of the water on the garden. I rode the 4-wheeler down and sat on it with my garden plan, comparing that glorious vision I created while planting seeds this spring to the few plants that the voracious grasshoppers have not eaten. I had used a biological control to try to control their numbers, mixing it fresh daily and spraying everything. Perhaps it worked; I may have killed millions of hoppers. But there were still billions and zillions in the garden.

We’ve had more grasshoppers here this year than I’ve ever seen. Neighbors who drive through have been shocked; I swear some rolled up their windows and sped out of the yard to avoid collecting any. By June the insects had eaten several successive plantings of radishes, lettuce, mesclun and carrots. They’d eaten the leaves from the rhubarb and were chomping down the stems. The kale and turnip leaves were lacy with holes and the hoppers were burrowing into the ground, eating the yellow onions. I replanted beans and peas three times and each time the hoppers ate them off as the seedlings emerged from the ground. They ate the potatoes down to the hay mulch and burrowed into it, still gnawing. By the millions they sliced the leaves from tomato plants, decimated the peonies and herbs– even the culinary sage. They even ate the perennial flowers I’d planted around the retreat house.

A month ago, I moved herb plants like basil, feverfew, rosemary, lavender, oregano and rue into the greenhouse. Despite tight screens, the grasshoppers invaded and dined until I moved the surviving plants into the house. Inside the cold frames, the hoppers stripped the peppers of all their leaves in one night.

In the prairie closest to my house, I’ve studied which of the native plants and the invasive nasty ones have survived the hopper onslaught. Natives like buffalo grass, sideoats grama, mullein, and gumweeds haven’t been nibbled at all. The Non-Native Nasties– introduced plants like brome, alfalfa and clover– have been stripped of their leaves and then their stems, though the plants survived. Unfortunately, non-natives that I cultivate, like columbine, peony, chamomile, arugula, marjoram, thyme and dill were decimated as well, though the bergamot and spearmint survived. Apparently even grasshoppers don’t eat creeping jenny, definitely one of the Nasty plants.

While I looked over the garden, I kept thinking of Lammas. How could I write about harvest with no produce? My summer had already been seriously unpoetic, with a variety of activities and responsibilities disrupting my writing.

Today, walking among the plants, I noticed that only a few hoppers leapt away from me, instead of the moving blanket of three weeks ago. Pulling bristly foxtail from the leek row and stuffing it into the burn barrel, I saw that the tomatoes are strong and blooming. The pumpkin vines sprawl and blossom, leaves shivering as entire rabbit families lounge in their shade. The kale and turnips are getting taller.

Back home, I examined the raised beds of my kitchen garden where the leafless tomato plants are bringing forth yellow Taxi tomatoes and tasty Early Girls. A couple of pots of basil and parsley so big I couldn’t move them inside are putting out new leaves.

Rather than focusing on its losses, the garden is working hard to recover from the failures of the summer. Maybe I can give thanks for some growth and this inspiration; maybe I have a subject for the harvest essay.

Sitting with my fingers on the keyboard, I glanced through the window in front of my desk and saw a bird I’d never seen before. I grabbed one of my bird books and tracked him down: a male orchard oriole. He landed in the raised tomato bed and then hopped to a tomato cage, tilting his head this way and that. He hopped. Hopped. Hopped again and snatched a grasshopper. Gobbled it and hopped some more– following and gulping hoppers as they tried to evade him.

Suddenly I understood. I’d been waiting for ideas for my Lammas essay to find me. Yet I’ve always known that writers sometimes have to chase ideas. We must be persistent; we must leap and snap and gobble— and sometimes fail to catch a tasty morsel. The oriole, by appearing outside my window, reminded me just how active a writer may have to be in chasing her ideas.

Later, I stepped outside and into a maelstrom of clucking and fluttering: two grown grouse and eleven teenagers were all scrambling around the dogs’ fenced yard, eating grasshoppers and chattering to one another. I went back to the computer.

My friends kindly say that I accomplish a lot, but they don’t see how much of what I do is part of avoiding this writing job I both love and find frustrating. Two big writing projects have been simmering in my brain all summer, but I’ve been able to work on them only in short bursts.

Naturally, yesterday and today I have spent considerable time answering email both urgent and frivolous, fixing and cleaning up after meals, cleaning bathrooms–the usual housewifely stuff. Yesterday I hand-wrote several letters. None of this was the writing I urgently need to do.

The need to post a new website essay related to writing hovered behind my thoughts like the afternoon thunderstorms: black and threatening. Each storm rattles the windows, throws any loose furniture around on the deck, and sneezes a few drops of rain: none of these actions very useful either to a gardener or a writer.

Because the air felt nippy when I woke at sunrise, I decided to enjoy some of the last of summer’s heat by tilling the garden. As I turned over the rich brown earth, I reflected on the meaning of Lammas. Also called Lughnasad by the ancients, it was traditionally commemorated only by women as a time of regrets and farewell as well as harvest and preservation.

Reflect, said the ancients, on regret and farewell, but also celebrate what you have worked hard to harvest and what you have preserved for your continuing life.

As Autumn comes, many people enact the ancient rituals of Lammas, but may be unaware that these celebrations reflect a long ancestral history. We may remember plans we made for summer, regretting that we have not accomplished everything. Frantically, we rush to cram a little more summer into the days. A tingle of chill in the air, like this morning’s 57 degrees, reminds us that winter is coming, so instead of whining about the heat, we revel in it as we harvest and preserve the fruits of our labors.

During Lammas, our ancestors paused to take note of their regrets for the things undone in summer. They said farewell to the summer’s activities while welcoming their harvests. Writers can observe the season in the same way as gardeners.

The Celts made this a fire festival, in recognition both of summer’s warmth and in preparation for the coming winter when they might need to conserve fuel as they huddled together around small fires, sharing warmth. If you wish to celebrate like the ancients, consider writing your regrets on paper or corn husks and tossing them into a bonfire so they vanish from your life. To celebrate harvest, share your garden’s fruits, perhaps baking rhubarb crisp or stirring up rhubarb sauce, or baking freshly-dug potatoes in that bonfire, surrounded by friends.

In the spirit of Lammas, then, I faced my failures: I have not yet finished the draft of what I’m calling the Wheel book. I have written that failure, among others, on a piece of paper. With the grasshoppers has come drought so the prairie here is tinder dry. Rather than risk building a bonfire outside, on August 1, I will light a candle in my study and carefully burn the record of this and other failures.

Writing down my failures has allowed me to become fully aware of my regrets for this season, so I can more easily let them go, both in my mind and through the fire’s symbolism. Furthermore, I realize that if I spend time brooding on what I failed to accomplish, or if I attempt to figure out why I did not do all that I wanted to do, I will be wasting time during which I could be writing.

Lammas asks us to consider farewells to whatever is passing from our lives. As a writer and human being, I welcome this prompting to say a firm goodbye to the things that are really over. Perhaps you can find visual symbols of what you regret— photos of that boyfriend who betrayed you? Throw them into a flame, or into moving water, or bury them in the ground.

Some folks bid loss farewell by whispering the hurt into flower bulbs, which they then plant. Symbolically, the pain returns in the spring transformed, in the form of a new and blooming life. Most of my plants are natives without bulbs, and many require freezing to be viable, so on my walks I collect seeds, and mumble my regrets as I scuff them into earth where I’d like them to thrive.

I’ve dug the potato crop, and we will eat all of it with our Lammas meal: five small potatoes. We will try not to think about last year’s crop, which supplied us with potatoes from September through May. This winter, we’ll have to peel the potatoes we eat since their skins harbor pesticides used by commercial farmers.

But on Lammas, we will rejoice in what we have and give thanks that we are not wholly dependent on our potato crop for nourishment this winter.

For the Celts, the August harvest was a time of story-telling, as well as giving thanks to the grain gods and goddesses in gratitude for a good harvest. Some folks find a visual way to represent their triumphs, perhaps creating a decoration like a corn dolly or wheat weaving like those made by ancient grain farmers, or creating an altar to represent the harvest. We reminisce about the garden’s toils and triumphs, and talk about what we might plant next year.

Inspired by the harvest aspect of Lammas, I list the things I have accomplished. In applying to the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, NV, I spent a lot of time writing a proposal for a workshop as well as preparing a CD with recitations of new poems. I’m disappointed that my application was rejected but I’ve revised the workshop to use in another context. So, while the application was a failure, I was able to recycle some of its materials, turning the whole experience into a positive one.

This year so far, I’ve written four home page messages, one each for February’s Brigid, the Vernal Equinox of March, April’s Beltane and the June Summer Solstice, a total of almost 9,000 words.

I wrote the introduction to a book (by a writer who has worked at my Windbreak House retreat) to be published by the South Dakota State Historical Society Press. I wrote a cover comment and review of another book. Observations about meat, grouse, natural predators, rabbits, organ meats, snakes and other prairie critters all furnished subjects for blogs on my business website. A college class reading my book No Place Like Home sent questions about the book to which I responded at length.

Further, I wrote two essays published in Orion magazine. Later, National Public Radio’s “Living on Earth” asked me to read them for on-air publication. A request for free writing advice turned into a lengthy blog on why I cannot and will not provide free advice to everyone who asks. On paper, I reflected on the fact that I am called a “nature writer”; I later submitted the essay to the International League of Conservation Writers, which published it online. Besides all this professional writing, I kept up lively correspondence with several friends, much of it in hand-written letters.

Compiling this list amazes me. Though I was determined not to regret what I have not written or done, I hadn’t fully realized how very much I have accomplished so far this year. Truly, my writing harvest has been generous. And I spent a lot of time in the garden, even though that harvest was less rich.

Besides writing, of course, I’ve prepared a couple of meals most days. Jerry cooks breakfast on weekends and we make our own breakfasts during the week. When we go to town, we usually eat lunch there. Let’s see: 365 days in a year multiplied by 3 meals a day is 1,095 meals. Deducting for the meals we fix ourselves or eat out, I’ve prepared at least 400 meals, perhaps as many as 700. I’ve washed the sheets 30 times, vacuumed the house at least 45 times, and cleaned the toilets at least 300 times. On Lammas, I will pat myself on the back for all this work.

Because Lammas is an occasion to consider preservation, both literal and symbolic preserves are appropriate for the Lammas festival. You celebrate when you turn summer’s fruit into jams, jellies, and chutneys for winter. Consider, too, other kinds of fruits– memories and scraps of writing– you have gathered this year. How can you preserve the memories of the summer that is passing sweetly even as winter approaches?

Don’t just put your photographs online; print them so you can look at them even when the computer is off— or when the file has been lost or hijacked, or you are old and in the nursing home without a computer. I’ve been told that creating physical photo albums is outmoded, but while my mother was in the nursing home, she found great pleasure in returning again and again to her old albums; she rediscovered memories each time. She would never have seen those photographs online. I framed a large collage of photographs of her at different phases of her life and we both enjoyed telling visitors about the times when the pictures were taken. I think all these activities helped her keep more clarity of mind than she might otherwise have had.

Lammas observances might include writing letters and postcards to friends instead of emails. Turn photos into postcards for short notes. Write memories in your journal. Capture the highlights: best meal of the summer, best sunrise, best day, best companion; you create the list.

Whatever you do– gardening, writing, or playing bridge– face your regrets and failures and then bid them goodbye. Consider how the earth recovers from winter into spring, taking heart for your own spring to come. Our planet is suffering in the current climate change crisis, but if hope exists, it rests on individuals like us. Take time to tally up your harvest, to revel in it, to appreciate your work. Then preserve it in your heart for the winter to come.

“Youth is like spring,” wrote Samuel Butler in The Way of All Flesh, “an over-praised season more remarkable for biting winds than genial breezes. Autumn is the mellower season, and what we lose in flowers we more than gain in fruits.” This is the message of Lammas.

Writing suggestions:

What do you regret about the summer just past? Can you discard those regrets by burning them symbolically or literally? Can you memorialize these regrets by writing about them, and diffusing their power over you?

What do you bid farewell to at summer’s end?

What have you harvested this year, either literally from the earth or from your work and your relationships?

What form of thanks seems appropriate for what you have received?

What ways can you find to preserve memories of your year’s harvest, and of memorable events from your year?

What was your best day during the summer? Your favorite event? Who is your favorite of the new people you met and why? This might be a good time to tell friends and relatives how much you appreciate something they’ve done for you, or how much you appreciate simply knowing them.

What have you accomplished in writing so far this year? What are your plans for writing during the rest of the year?

Collect the snippets you have written this year that have not progressed to a longer draft or a finished work. Read through them; take notes. What inspiration do you find?

Here’s a specific exercise for not writing: The Ball of Light

Stand outside where you will not be disturbed. Plant your feet a comfortable distance apart so you stand without swaying. Let your hands hang at your sides; shake them to loosen the muscles in your shoulders.

Close your eyes. Breathe deeply several times. Imagine yourself drawing air in from the entire universe, pulling it down into your lungs, fingertips, toes, into every molecule of your body.

Imagine a ball of light centered in your chest. Gather your senses into the ball of light. Imagine your hands inside your chest holding the light, firming it into a smooth round shape. When you have the ball of light pictured clearly in your mind, let it rise slowly up your neck into your head. Let it stand there, spinning, for a moment. Slowly move it up through the top of your skull and above your head. Take time to look down at your body standing relaxed, to breathe deeply again. Then concentrate your attention in your light again and let it rise up over the grass and the buildings. Pause every now and then to look around so you always know where you are.

Allow your light to rise over your immediate surroundings, up over the country, above the path of jet planes, out where the universe is blackness lit only by stars and where you might see other glowing balls of light. Become aware of what you see and sense there. Slowly bring the ball of light back down through all the layers of atmosphere to your chest and belly again. Breathe deeply.

Once you have done this a few times, you can do it anywhere, anytime, in less time than reading these paragraphs. Use this as a relaxation and centering exercise anytime. You may find that you are more ready to write afterward.

Remember this: Graham Greene realized early in his writing career that if he wrote just 500 words a day, he would have written several million words in a few decades. So he developed a habit of writing only 500 words a day and stopping even if he was in the middle of a sentence. Writing two hours a day, he published 26 novels, as well as short stories, plays, screenplays, memoirs and travel books.

Kathleen Norris writes in Dakota that “the forced observation of little things can also lead to simple pleasures,” and illustrates this with the example of a young monk who was given an old, worn habit when he joined his order. He soon discovered that the worn wool was excellent for sliding down banisters.

Adapt this idea for sliding down the banisters in your life. Carefully observe and note down the little things you do every day: picking up the children’s socks, folding your husband’s clothes, petting the dog, and wiping up the drops of water around the sink after brushing your teeth. Then consider and write about the reason you do these things. If the reason is not because you care for the individuals and care for the home in which your love for them occurs, then perhaps you can stop doing them. Write about this choice.

# # #

The Wheel of the Year is structured with sixteen essays, one for each of the eight seasons through two years, with an intermission essay, “Respect Writing By Not Writing,” which discusses taking time off. Extensive writing suggestions are included, as well as additional resources. The workbook is intended as a guide and teacher as a writer sets up her own schedule of writing and develops a relationship with the natural and mundane worlds in which we live. If the reader came to a retreat at my Windbreak House Retreats, this might be a series of conversations we would have about writing.

I have sold nearly all of my copies of the book, though I believe it can still be found online. I plan to create a revised version in the next year or so in order to correct a number of publisher’s errors. I will work with the same editor who did the lovely layout of my book Write Now, Here’s How: Insights from Six Decades of Writing.

Once I have the revised edition I will announce it here and on my Facebook page.

Linda M. Hasselstrom

Windbreak House Writing Retreats

Hermosa, South Dakota

© 2022, Linda M. Hasselstrom

# # #

Today’s the day, I promised myself this morning, just as I did yesterday and the day before.

Today’s the day, I promised myself this morning, just as I did yesterday and the day before. Finally I sat down at the computer– and immediately decided I needed to change the location of the water on the garden. I rode the 4-wheeler down and sat on it with my garden plan, comparing that glorious vision I created while planting seeds this spring to the few plants that the voracious grasshoppers have not eaten. I had used a biological control to try to control their numbers, mixing it fresh daily and spraying everything. Perhaps it worked; I may have killed millions of hoppers– but billions and zillions more arrived.

Finally I sat down at the computer– and immediately decided I needed to change the location of the water on the garden. I rode the 4-wheeler down and sat on it with my garden plan, comparing that glorious vision I created while planting seeds this spring to the few plants that the voracious grasshoppers have not eaten. I had used a biological control to try to control their numbers, mixing it fresh daily and spraying everything. Perhaps it worked; I may have killed millions of hoppers– but billions and zillions more arrived.

Back home, I examined the raised beds of my kitchen garden where the leafless tomato plants are bringing forth yellow Taxi tomatoes and tasty Early Girls. A couple of pots of basil and parsley so big I couldn’t move them inside are putting out new leaves.

Back home, I examined the raised beds of my kitchen garden where the leafless tomato plants are bringing forth yellow Taxi tomatoes and tasty Early Girls. A couple of pots of basil and parsley so big I couldn’t move them inside are putting out new leaves. Suddenly I understood. I’d been waiting for ideas for my Lammas essay to find me. But I know that writers sometimes have to chase ideas. We must be persistent; we must leap and snap and gobble– and sometimes fail to catch a tasty morsel. The oriole, by appearing outside my window, reminded me just how active a writer may have to be in chasing her ideas.

Suddenly I understood. I’d been waiting for ideas for my Lammas essay to find me. But I know that writers sometimes have to chase ideas. We must be persistent; we must leap and snap and gobble– and sometimes fail to catch a tasty morsel. The oriole, by appearing outside my window, reminded me just how active a writer may have to be in chasing her ideas.

Because the air felt nippy when I woke at sunrise, I decided to enjoy some of the last of summer’s heat by tilling the garden. As I turned over the rich brown earth, I reflected on the meaning of Lammas. Also called Lughnasad by the ancients, it was traditionally commemorated only by women as a time of regrets and farewell as well as harvest and preservation.

Because the air felt nippy when I woke at sunrise, I decided to enjoy some of the last of summer’s heat by tilling the garden. As I turned over the rich brown earth, I reflected on the meaning of Lammas. Also called Lughnasad by the ancients, it was traditionally commemorated only by women as a time of regrets and farewell as well as harvest and preservation.

For the Celts, the August harvest was a time of story-telling, as well as giving thanks to the grain gods and goddesses in gratitude for a good harvest. Some folks find a visual way to represent their triumphs, perhaps creating a decoration like a corn dolly or wheat weaving like those made by ancient grain farmers, or creating an altar to represent the harvest. We reminisce about the garden’s toils and triumphs, and talk about what we might plant next year.

For the Celts, the August harvest was a time of story-telling, as well as giving thanks to the grain gods and goddesses in gratitude for a good harvest. Some folks find a visual way to represent their triumphs, perhaps creating a decoration like a corn dolly or wheat weaving like those made by ancient grain farmers, or creating an altar to represent the harvest. We reminisce about the garden’s toils and triumphs, and talk about what we might plant next year.

On the day that I read this article, I received a call from poet Wally McRae, the reigning king of Cowboy Poetry. I’d sent him a copy of my collection Dakota: Bones, Grass, Sky, published by Spoon River Poetry Press in 2017. I didn’t ask or expect a review from Wally. Still, I thought he might enjoy or be inspired by some of the poems, especially since Wally believes all poetry should rhyme, and most of mine do not.

On the day that I read this article, I received a call from poet Wally McRae, the reigning king of Cowboy Poetry. I’d sent him a copy of my collection Dakota: Bones, Grass, Sky, published by Spoon River Poetry Press in 2017. I didn’t ask or expect a review from Wally. Still, I thought he might enjoy or be inspired by some of the poems, especially since Wally believes all poetry should rhyme, and most of mine do not. I could hear him turning pages as he spoke, and soon he mentioned more poems he liked: “Handbook to Ranching,” another poem dedicated to my father, beginning with one of his strongest rules: “Don’t spend any money.”

I could hear him turning pages as he spoke, and soon he mentioned more poems he liked: “Handbook to Ranching,” another poem dedicated to my father, beginning with one of his strongest rules: “Don’t spend any money.”

My comp copy of Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness & Connection arrived yesterday, and I’ve gotten behind on the news (thank goodness!) because I keep picking it up to read another fine poem.

My comp copy of Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness & Connection arrived yesterday, and I’ve gotten behind on the news (thank goodness!) because I keep picking it up to read another fine poem. I’ve spent my writing life extolling the virtues of the gorgeous grasslands of the Great Plains, which furnish a considerable amount of the air we breathe. They also furnish grazing for grassfed beef, and thus are important to all of us for a variety of reasons, most of which I’ve explained at length in nonfiction and poetry in 17 published books.

I’ve spent my writing life extolling the virtues of the gorgeous grasslands of the Great Plains, which furnish a considerable amount of the air we breathe. They also furnish grazing for grassfed beef, and thus are important to all of us for a variety of reasons, most of which I’ve explained at length in nonfiction and poetry in 17 published books.

So I try to outsmart myself, to insist on keeping writing central to my daylight schedule. Moving from household job to mundane task, I carry my journal. Jobs like peeling potatoes and wrapping gifts allow my mind to delve into ideas for next season’s writing, and my journal is right there on the kitchen counter where I can make notes. Yes, some pages are smeared with potato juice or tomato sauce; those decorations add specific memories when I return to the notes!

So I try to outsmart myself, to insist on keeping writing central to my daylight schedule. Moving from household job to mundane task, I carry my journal. Jobs like peeling potatoes and wrapping gifts allow my mind to delve into ideas for next season’s writing, and my journal is right there on the kitchen counter where I can make notes. Yes, some pages are smeared with potato juice or tomato sauce; those decorations add specific memories when I return to the notes!

Writing in the journal, too, can enlighten as well as discipline a writer. When the dogs wake me between four and five in the morning, I let them out, record the temperature, and let them back in. Then I sit against pillows in bed, the dogs beside me, and pick up my journal. At that moment, I may have no conscious idea of what to write beyond “12/2/10 4:35 a.m. 25 degrees.” Once I have recorded those traditional details, though, I have limbered my mind and pen and may write about a dream, or thoughts from wakeful moments in the night or the sunrise and the heron looking for frogs in the pond outside the window.

Writing in the journal, too, can enlighten as well as discipline a writer. When the dogs wake me between four and five in the morning, I let them out, record the temperature, and let them back in. Then I sit against pillows in bed, the dogs beside me, and pick up my journal. At that moment, I may have no conscious idea of what to write beyond “12/2/10 4:35 a.m. 25 degrees.” Once I have recorded those traditional details, though, I have limbered my mind and pen and may write about a dream, or thoughts from wakeful moments in the night or the sunrise and the heron looking for frogs in the pond outside the window. Outside my study window stands my new greenhouse. With its curved, pointed roof, it reminds me of the tiny retreats used for meditation by Eastern monks. Half-laughing at myself, I dashed through falling snowflakes into the greenhouse and sat on an ancient stool my mother had painted blue so long ago the paint is cracked.

Outside my study window stands my new greenhouse. With its curved, pointed roof, it reminds me of the tiny retreats used for meditation by Eastern monks. Half-laughing at myself, I dashed through falling snowflakes into the greenhouse and sat on an ancient stool my mother had painted blue so long ago the paint is cracked.

The Wheel of the Year: A Writer’s Workbook (2015, Red Dashboard) is structured with sixteen essays, one for each of the eight seasons through two years, with an intermission essay, “Respect Writing By Not Writing,” which discusses taking time off. Extensive writing suggestions are included, as well as additional resources. The workbook is intended as a guide and teacher as a writer sets up her own schedule of writing and develops a relationship with the natural and mundane worlds in which we live. If the reader came to a retreat at my Windbreak House Writing Retreats, this might be a series of conversations we would have about writing.

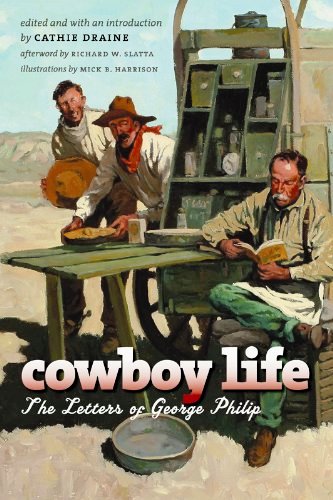

The Wheel of the Year: A Writer’s Workbook (2015, Red Dashboard) is structured with sixteen essays, one for each of the eight seasons through two years, with an intermission essay, “Respect Writing By Not Writing,” which discusses taking time off. Extensive writing suggestions are included, as well as additional resources. The workbook is intended as a guide and teacher as a writer sets up her own schedule of writing and develops a relationship with the natural and mundane worlds in which we live. If the reader came to a retreat at my Windbreak House Writing Retreats, this might be a series of conversations we would have about writing. Cowboy Life: the Letters of George Philip, edited and with an introduction by Cathie Draine; afterword by Richard W. Slatta; illustrations by Mick B. Harrison. South Dakota State Historical Society Press, (Pierre, S.D.) 2007.

Cowboy Life: the Letters of George Philip, edited and with an introduction by Cathie Draine; afterword by Richard W. Slatta; illustrations by Mick B. Harrison. South Dakota State Historical Society Press, (Pierre, S.D.) 2007. Deftly, Philip shoots down every myth about cowboys, insisting on a realistic view of the work done. “Although it now seems to be part of the blood lust of the spectators in their demands on the performers at the rodeos,” he writes on August 16, 1940, “it was no part of a cowhand’s business to ride cattle of any sort.” Cattle are supposed to make money for their owner, and riding them wears off fat and makes them wild. Philip’s point about care for the cattle made, he proceeds to recall an occasion when a collection of wild range steers tossed on their ears cowboys who later became respectable citizens, all of whom he names.

Deftly, Philip shoots down every myth about cowboys, insisting on a realistic view of the work done. “Although it now seems to be part of the blood lust of the spectators in their demands on the performers at the rodeos,” he writes on August 16, 1940, “it was no part of a cowhand’s business to ride cattle of any sort.” Cattle are supposed to make money for their owner, and riding them wears off fat and makes them wild. Philip’s point about care for the cattle made, he proceeds to recall an occasion when a collection of wild range steers tossed on their ears cowboys who later became respectable citizens, all of whom he names. Cathie Draine, who edited this book so brilliantly, is the granddaughter of the letters’ author, George Philip; her astonishing grandfather would be proud of her. A retired teacher and freelance writer, she often writes for the Rapid City Journal. She provided the staff of the South Dakota Historical Society Press with notes from her voluminous research that helped them create almost fifty pages of chapter notes that are among the most useful I’ve ever seen, defining terms, providing further resources, and furnishing explanations.

Cathie Draine, who edited this book so brilliantly, is the granddaughter of the letters’ author, George Philip; her astonishing grandfather would be proud of her. A retired teacher and freelance writer, she often writes for the Rapid City Journal. She provided the staff of the South Dakota Historical Society Press with notes from her voluminous research that helped them create almost fifty pages of chapter notes that are among the most useful I’ve ever seen, defining terms, providing further resources, and furnishing explanations.