All that apprehension—for what? I ride in the palm of an unseen hand that gently deposits me in places like this—a waystation for my soul—a soft place to land at a turning point.

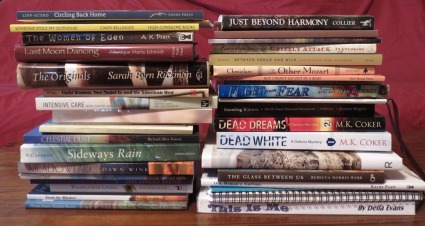

If a writer asks me to decide whether to continue writing or give up, I always refuse; no one can judge how much help the act of writing might provide to an individual, even if no single word ever appears in print. I will help a writer improve her work, and suggest possibilities for publishing, but no one can guarantee publication or declare that it is impossible. I remind them that my opinion may not be correct, but I’ve been able to appreciate something in the work of every writer with whom I’ve worked.

If a writer asks me to decide whether to continue writing or give up, I always refuse; no one can judge how much help the act of writing might provide to an individual, even if no single word ever appears in print. I will help a writer improve her work, and suggest possibilities for publishing, but no one can guarantee publication or declare that it is impossible. I remind them that my opinion may not be correct, but I’ve been able to appreciate something in the work of every writer with whom I’ve worked.

To my delight, the expansion of “social media” during the past twenty years allows me to tell many of these writers they probably can find an audience online, if nowhere else.

And, especially, Linda gave me the courage to think these words and now to state them publicly and in writing, “I am a writer.” Whew!

More importantly, though, I want writers to understand that writing isn’t just about publishing. This is a difficult concept to teach, especially since I have been published; a writer may think I’m being dishonest. I tell them about many occasions when the writing itself satisfied my need to tell the story, particularly if there are compelling reasons why it should not be published: it would embarrass me with someone still living, or it is too personal to reveal. The writing is the important part.

I came here feeling stressed, angry and depressed, ready to quit writing. I leave here renewed, centered and excited about new writing projects. Thank you from my heart and spirit dear sister friend.

At some retreats elsewhere, a famous visiting writer is the lure for customers. The visitor may lecture on various aspects of the writing business, or conduct a workshop by providing a list of writing prompts. The writing students may come without any particular plan and write for a few minutes at someone else’s direction. While these practices may inspire serious writing, I find the structure too much like a flashback to English class. The visiting writer cannot, and usually is not asked to, comment extensively on the drafts produced, and will likely never encounter the writing students again. The writers may take the topic seriously and write as well as possible in an hour or two, but fail to find the incentive to continue working on the draft after the class is over.

The vastness, the openness of the landscape requires the same in me. I saw a limb on the west side of a juniper bent around the trunk to become a limb on the east side of the tree, and why not? If the prevailing winds beat the crap out of you, try another way. A cow farted during the meditation just to keep me down to earth.

On July 19-22, 1996 I referred to the first retreat in the house journal as a “workshop.” I soon dropped that term because it led writers to assume they would be given a series of writing assignments, as is the case at some retreats. Instead, I wanted writers to select what they wanted to learn, and work with me to learn it rather than me lecturing as if I am an expert.

I came to this place seeking a stronger sense of myself. I told myself that if I learned more about writing it would be a bonus. Knowing that I left home very tired, mentally scattered and unsure of what role I wanted to make foremost in my life, I wanted this to be special. It was.

My method is simple. I ask each writer to send to me in advance the writing that they want to work on during the retreat. Now that it’s possible, I prefer this writing be sent electronically, so that I can download it to a flash drive. Then I carefully read each submission several times, writing my comments right in the manuscript.

My method is simple. I ask each writer to send to me in advance the writing that they want to work on during the retreat. Now that it’s possible, I prefer this writing be sent electronically, so that I can download it to a flash drive. Then I carefully read each submission several times, writing my comments right in the manuscript.

Thanks for offering me a chance I’ve never had: to be critiqued.

As I read, I think of various ways to reinforce my message. For example, if I read this line, “While wondering about this phenomenon, the sun sank from view. . . .”

I will write to the author that this is an example of a dangling modifier. The effect of the dangling phrase is to make the noun following it the subject of the opening phrase, so the author has really written that the sun is wondering about a phenomenon while it sinks from view. Correction means providing a subject: “While I was wondering . . . , the sun  sank from view.” Then I attach to the writer’s manuscript my handout on dangling modifiers, already prepared with examples of the error and how to correct it. By providing this additional information, I’m offering the writer an opportunity to learn enough about the error to avoid it in future writing: as if we’d had a full class on dangling modifiers.

sank from view.” Then I attach to the writer’s manuscript my handout on dangling modifiers, already prepared with examples of the error and how to correct it. By providing this additional information, I’m offering the writer an opportunity to learn enough about the error to avoid it in future writing: as if we’d had a full class on dangling modifiers.

While I was on vacation this summer, I read all of the handouts you gave me, and felt as though I’d returned to retreat for a little while.

I think Windbreak House is unique because I am here as a full-time resident writer. I ask writers to come with a plan for what they want to accomplish during the retreat, and my primary purpose is to help each writer reach her goals. We work one-on-one, though if other writers are in residence, they may decide to work together.

Gushing thanks for the most valuable, in-depth critique of my writing thus far in this life.

If I’m asked, I’ll provide suggestions for writing topics, but I prefer to let each writer choose her own direction. Often our work together means we remain in contact for months or years, as I continue to offer advice and encouragement.

From you, I learned that writing poetry is not simply coming up with inspirational words on the page. Almost immediately, you led me back to the practice of research which, ironically, is where I started my career years ago. I have discovered again the love of looking up facts, questing for the details that make writing enjoyable to read.

One of my most useful writing tools has been my journal, and I believe strongly in the power of journaling to aid self-discovery. Write fiercely in your journal, I say, write recklessly. Do not let your inner editor slow you down. Do not channel that English teacher in high school who always found an error. Don’t think about spelling or grammar or how this will look in print. Emote. Stomp through the words. Fling handfuls of syllables in the air and let them land on your paper. Often the heat of the anger or the pain of the loss or the joy of the new love will inspire the perfectly correct words that will never emerge if you think “someone is going to read this.” Journals must be private; no one should read your journal any more than a stranger can pry open your brain and look inside. Your journal is your freedom, your inspiration, your guide, and ultimately your resource.

One of my most useful writing tools has been my journal, and I believe strongly in the power of journaling to aid self-discovery. Write fiercely in your journal, I say, write recklessly. Do not let your inner editor slow you down. Do not channel that English teacher in high school who always found an error. Don’t think about spelling or grammar or how this will look in print. Emote. Stomp through the words. Fling handfuls of syllables in the air and let them land on your paper. Often the heat of the anger or the pain of the loss or the joy of the new love will inspire the perfectly correct words that will never emerge if you think “someone is going to read this.” Journals must be private; no one should read your journal any more than a stranger can pry open your brain and look inside. Your journal is your freedom, your inspiration, your guide, and ultimately your resource.

So besides the work they show to me, I hope that writers will keep their own private journals and write in them daily. Each writer may write as often as she likes in the house journal.

You inspire me, teach me and give me the tools I need to be a better writer. I suppose if I looked back over this journal entry I could knock out at least 20 wordy words, correct my commas and do some rearranging.

Writers come here engrossed in their own stories, so my job is to ask the questions about what they are doing that will help them accomplish their goals. How did they arrive at their conclusions? My aim is to help them articulate ideas they may have accepted without debate, thus benefiting both of us and leading to absorbing discussions about all kinds of topics.

My family would have me committed if they knew that I drove 6 hours from my mother’s to sit on a hill and write. . . . what they don’t understand is that I needed Linda and [another writer at the retreat] to reinforce and to encourage me. I needed to be away from the noise of my family. . . . On the hill, for the first time ever, I wrote about what used to be a taboo topic.

Lively writing discussions may begin in a one-on-one discussion as I comment on the writer’s work, continue to the kitchen as we fix lunch, progress through our meal and move to the living room, or to chairs scattered around the house. We often hike in the surrounding pastures, crawling under or through barbed wire fences, watching for rattlesnakes and wildlife as we discuss writing and I explain our ranching practices.

Thanks for showing us how to braid words.

Writers are often fearful of the consequences of writing about ugly events like abuse or divorce or drunkenness in their families. My advice is to write it down, every bit of it that they remember or believe, and then decide what to do with it. Perhaps writing it down will allow you to banish the worst memories from your mind. Some writers burn the resulting manuscript, symbolically destroying the memory. Others change the names of the people involved and work toward publishing in order to help others who confront the same problems. Those decisions can’t be made until you see what you have written, and how you feel once it’s on paper.

One bulletin board holds buttons: “Hatred is not a family value,” and “If you settle for what they’re giving you, you deserve what you get.”

Yesterday I wore the button, “What part of YES are you afraid of.” Wrote in my journal, “All of it!” Tomorrow I hope to leave with “Not all who wander are lost” imprinted on my soul.

Many writers, perhaps remembering those red ink remarks from English teachers, worry about writing everything correctly, with perfect grammar and spelling. Some fear appearing sentimental or not emotional enough, or being too stiff and objective. Some subjects and publishing opportunities do require detachment, but before you can begin editing for factual content, you need a draft to work with. To them I quote William Stafford who said, “Lower your standards and keep writing!”

Our final conversation re: emotion was equally as valuable. After stewing over my bent for objectivity and feeling the failure for not emoting on paper, I realize my reserve is not wrong, not “bad.” Too many today haven’t learned that restraint is a virtue—when used appropriately.

Most of the writers want to establish regular writing schedules but families and jobs and the business of life interfere with their writing. At the end of each retreat, we discuss what will happen when the writer gets home. How can she carve writing time from her normal agenda? I gently suggest that it may not be realistic to decide to get up at 5 a.m. every Saturday and write for two hours before making pancakes for the kiddies. We discuss how setting unrealistic goals can lead to failure.

I’ve never committed myself to such an intense time of writing because I’ve never considered myself a “real” writer—just a writing teacher. This experience made me feel like I am one, even if I may never be published.

Of course I, too, still have trouble setting priorities. What do I really need to do today, and what is a job I’m doing simply to avoid tough writing? I remind them that while it’s important to maintain a steady writing practice, it’s equally important not to waste time berating yourself when you fail. Just keep working at it. If you punish yourself for failing to write, you will begin to associate writing with the punishment.

Within the house I can also see, feel and learn from all of the other people who have visited here in the past.

To be continued . . .

Linda M. Hasselstrom

Windbreak House Writing Retreats

Hermosa, South Dakota

© 2017, Linda M. Hasselstrom

# # #

Author’s note: I wanted Windbreak House writers to speak for themselves in this review of twenty years. Unless they are otherwise identified, all comments in italics are from the Windbreak House journals, written by writers at the conclusion of their retreats.

Writing is not the only art celebrated and practiced here. One woman played her guitar in the living room after supper, inviting a singalong. A writer who had studied the Japanese art of ikebana created an arrangement of stones, grandmother cedar, a weathered plank, juniper, native stone and grasses that symbolized her experience at the retreat, and brought peaceful symmetry to the house for months. Other guests, unfamiliar with the art, moved it from one room to another, wrote about it, photographed and studied it. One man wrote a postcard to the creator, expressing his astonishment and delight at finding the ikebana in his room. I mailed it for him since I felt it would be unethical to reveal her address.

Writing is not the only art celebrated and practiced here. One woman played her guitar in the living room after supper, inviting a singalong. A writer who had studied the Japanese art of ikebana created an arrangement of stones, grandmother cedar, a weathered plank, juniper, native stone and grasses that symbolized her experience at the retreat, and brought peaceful symmetry to the house for months. Other guests, unfamiliar with the art, moved it from one room to another, wrote about it, photographed and studied it. One man wrote a postcard to the creator, expressing his astonishment and delight at finding the ikebana in his room. I mailed it for him since I felt it would be unethical to reveal her address. For the record, vegetarians are welcome in this beef-raising haven, though I do not care for the smell of boiling carrageen moss. My acceptance of writers to work here is based solely on their writing, and whether I believe I can help them, not on their profession or anything else I might know about them.

For the record, vegetarians are welcome in this beef-raising haven, though I do not care for the smell of boiling carrageen moss. My acceptance of writers to work here is based solely on their writing, and whether I believe I can help them, not on their profession or anything else I might know about them. Most writers attend alone, or in clusters of two or three, but group retreats have included graduate students and teachers from various universities who brought tents so that the guests who couldn’t fit into the house could camp among the trees. During their stay they hiked in the Black Hills and I talked about writing and responsible cattle ranching on the shortgrass prairie.

Most writers attend alone, or in clusters of two or three, but group retreats have included graduate students and teachers from various universities who brought tents so that the guests who couldn’t fit into the house could camp among the trees. During their stay they hiked in the Black Hills and I talked about writing and responsible cattle ranching on the shortgrass prairie.

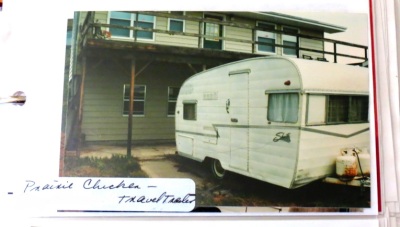

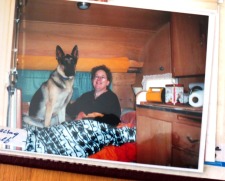

Once, when a fire in the forested hills poured smoke and ashes down on Tamara’s house during a retreat, she took refuge in the travel trailer with her German shepherd. I was startled awake by a deep “WOOF!” at sunrise.

Once, when a fire in the forested hills poured smoke and ashes down on Tamara’s house during a retreat, she took refuge in the travel trailer with her German shepherd. I was startled awake by a deep “WOOF!” at sunrise. Once a writer walked up the retreat house steps carrying mounted head of a buck deer. On her way to the retreat she’d been touring a second-hand store, she said, and he looked lonely, so she brought him along; she named him Timothy, and he supervised her writing week. She later said that when she was stopped for speeding on the way home, she thought the sight of Timothy in the passenger seat meant the difference between a ticket and the warning she got.

Once a writer walked up the retreat house steps carrying mounted head of a buck deer. On her way to the retreat she’d been touring a second-hand store, she said, and he looked lonely, so she brought him along; she named him Timothy, and he supervised her writing week. She later said that when she was stopped for speeding on the way home, she thought the sight of Timothy in the passenger seat meant the difference between a ticket and the warning she got.

One retreat writer sent me a quilt made by her mother. We use it regularly in Eagle, and she assured us that it’s durable, so if we wear it out, she’d send another. Other quilters have given the retreat house decorative hangings inspired by their time here.

One retreat writer sent me a quilt made by her mother. We use it regularly in Eagle, and she assured us that it’s durable, so if we wear it out, she’d send another. Other quilters have given the retreat house decorative hangings inspired by their time here. Another writer had bought a batch of quilt pieces in a second-hand store on her way to retreat, and enjoyed having space enough to lay them out on the floor to see their pattern, as preparation for writing about them.

Another writer had bought a batch of quilt pieces in a second-hand store on her way to retreat, and enjoyed having space enough to lay them out on the floor to see their pattern, as preparation for writing about them.

We also have a Blizzard Policy; if a blizzard is severe enough that the writer can’t drive to the highway, or the highways are closed, all the days during which you can’t leave are without charge. If the writer didn’t bring enough food, my freezers are always full. Several writers tell me they now watch weather reports, hoping to schedule retreats during a major winter storm.

We also have a Blizzard Policy; if a blizzard is severe enough that the writer can’t drive to the highway, or the highways are closed, all the days during which you can’t leave are without charge. If the writer didn’t bring enough food, my freezers are always full. Several writers tell me they now watch weather reports, hoping to schedule retreats during a major winter storm. At first, I envisioned the retreat as being so harmonious that I would not need to set rules. Each group of guests, I supposed, would decide the mood of the retreat among themselves. Civilized women shouldn’t need a handbook or a set of Dos and Don’ts. Surely, I thought, the women who came to a writing retreat would be experienced at publishing, needing only a quiet place and some gentle guidance to turn out page after page of brilliant writing.

At first, I envisioned the retreat as being so harmonious that I would not need to set rules. Each group of guests, I supposed, would decide the mood of the retreat among themselves. Civilized women shouldn’t need a handbook or a set of Dos and Don’ts. Surely, I thought, the women who came to a writing retreat would be experienced at publishing, needing only a quiet place and some gentle guidance to turn out page after page of brilliant writing. The house has no rule of silence, but I encourage respectful quiet, suggesting that residents turn off their phones. If they are worried about emergencies, I tell them how their loved ones can reach the local Sheriff if they need to contact us. Some just check their messages once a day and do not respond. Once in a while a writer uses a smart phone to go online, but the retreat house has no internet connection. Getting disconnected from these daily distractions can make a huge difference in a writer’s life, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for some; a few have been astonished that I’d even suggest it. Most are later grateful.

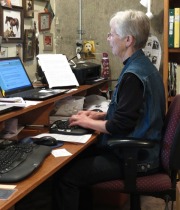

The house has no rule of silence, but I encourage respectful quiet, suggesting that residents turn off their phones. If they are worried about emergencies, I tell them how their loved ones can reach the local Sheriff if they need to contact us. Some just check their messages once a day and do not respond. Once in a while a writer uses a smart phone to go online, but the retreat house has no internet connection. Getting disconnected from these daily distractions can make a huge difference in a writer’s life, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for some; a few have been astonished that I’d even suggest it. Most are later grateful. When I have an idea, it’s easy to write furiously: I take notes in my journal, I mumble to myself and take more notes while walking the dogs, and I sit at the computer and type wildly. Once I’m immersed in a project, my subconscious mind keeps working while I get lunch started, answer an email or two. At night, in order to stop thinking about the writing, I read a mystery until I fall asleep.

When I have an idea, it’s easy to write furiously: I take notes in my journal, I mumble to myself and take more notes while walking the dogs, and I sit at the computer and type wildly. Once I’m immersed in a project, my subconscious mind keeps working while I get lunch started, answer an email or two. At night, in order to stop thinking about the writing, I read a mystery until I fall asleep. As soon as I’d made the decision to turn my ranch house into a writing retreat, I started coming back to the ranch more often to help my assistant, Tamara, get ready to make the plan a reality. She provided unlimited energy and creative ideas, as well as hard labor. She recalls “mowing the huge yard (and the wonderful varied odors as I cut the different plants that had been baking in the sun), painting the rooms, putting weatherproofing stain on the deck.”

As soon as I’d made the decision to turn my ranch house into a writing retreat, I started coming back to the ranch more often to help my assistant, Tamara, get ready to make the plan a reality. She provided unlimited energy and creative ideas, as well as hard labor. She recalls “mowing the huge yard (and the wonderful varied odors as I cut the different plants that had been baking in the sun), painting the rooms, putting weatherproofing stain on the deck.” Analyzing my one-family house for its suitability as a retreat, we decided that visiting writers would occupy the main floor, sharing the kitchen, dining room, living room and bathroom. We named the master bedroom Eagle in honor of a Daniel Long Soldier painting. A smaller bedroom became Dragonfly after a colorful print. My study was already established in the walk-out basement, abutted by a half-bath with its walls lined with bookshelves. I created a single bed by putting a door across two antique trunks and adding a foam mattress. Tam dubbed the place Burrowing Owl after my favorite prairie owl, which lives in old prairie dog burrows.

Analyzing my one-family house for its suitability as a retreat, we decided that visiting writers would occupy the main floor, sharing the kitchen, dining room, living room and bathroom. We named the master bedroom Eagle in honor of a Daniel Long Soldier painting. A smaller bedroom became Dragonfly after a colorful print. My study was already established in the walk-out basement, abutted by a half-bath with its walls lined with bookshelves. I created a single bed by putting a door across two antique trunks and adding a foam mattress. Tam dubbed the place Burrowing Owl after my favorite prairie owl, which lives in old prairie dog burrows.