One day in May I realized that I was going to be alone in my house— except for my dogs— for several days. I wrote in my journal and on my Facebook page:

Today I am starting a personal retreat to get back to a working routine after ten days of travel, meetings, illness, pain, a spring snowstorm, and various other disruptions.

I began this retreat by opening a gift sent to me by my friend January Greenleaf, a TED talk by lexicographer Erin McKean. Make time for yourself, for your enlightenment and education, to listen for fifteen minutes. For more information: www.erinmckean.com, which lists various places you can learn more about her projects, which include wordnik, where you can look up words and phrases; VERBATIM, a language quarterly; The Word column for the Boston Globe; her varied blogs, (which include one called A Dress a Day, detailing the dresses she makes and proving that an obsession with words doesn’t mean she doesn’t have other interests), her biography, and contact information.

My retreat was already well begun. At 4:30 that morning, I’d awakened with the dogs, let them outside, started the coffee, let them back in, and settled in bed with my journal. I wrote a plan for the retreat week, had breakfast and fed the dogs.

My retreat was already well begun. At 4:30 that morning, I’d awakened with the dogs, let them outside, started the coffee, let them back in, and settled in bed with my journal. I wrote a plan for the retreat week, had breakfast and fed the dogs.

As soon as I declared myself “on retreat.” I felt more relaxed. Simply making the declaration meant I had time— when in reality I had made time by making the decision.

I stretched. I walked the dogs, I rinsed my few breakfast dishes and put them beside the sink. Finally I went to my office. My retreat plan prohibited me from checking email until late in the afternoon, but I knew the video was waiting for me and thought it might be a good way to focus my attention on writing, so I allowed myself to go online long enough to watch it before shutting down my Internet connection.

At last I was ready to begin the first writing task I’d assigned myself: writing about creating a short retreat at home— while creating a short retreat at home.

My first suggestion for creating a private retreat is to choose to do so. Decide how long your retreat will last, and begin to create the conditions that will help you make the best use of that retreat.

Prepare for your retreat: physical space

Most of us have developed a lifestyle built around events that are really distractions from real life, so we may behave as though this disorganization is normal. Email notifications appear on our computers; our cell phones ring; we run to the store for milk; people say “are you busy?” and without waiting for a reply launch into a recitation of their troubles. By planning ahead, you may be able to immerse yourself in work more fully than you can on a normal day. Depending on your circumstances, you might:

–tidy the house so you won’t be tempted to clean while retreating

–cook or arrange for several meals in advance

–inform friends you will be limiting email and phone calls

–arrange your workspace to focus on your primary project; put aside temptations that might distract you from your main job

–remove potential disturbances: turn off your cell phone; put a note on the TV that says “NO!” A friend shuts off her computer’s audio speaker so she doesn’t hear the ding of incoming emails.

–remove potential disturbances: turn off your cell phone; put a note on the TV that says “NO!” A friend shuts off her computer’s audio speaker so she doesn’t hear the ding of incoming emails.

–pull shades and lock doors if you have friends who “drop in;” one writer I know hides in a vine-covered alcove in her back yard, out of sight from six feet away, and unable to hear the telephone in the house or the door bell.

–if you don’t live alone, explain the terms of your retreat to other members of the household and arrange for them to do the necessary chores you usually do.

–If you cannot be alone in your house during your retreat, make the quiet statement of a closed door. Since my study door usually stands open, my partner knows, when he sees it shut, not to knock, call out, or open it. And if my sneaky mind tries to distract me from my work, I’m reminded of my purpose as soon as I grasp the doorknob.

Prepare for your retreat: mental space

These are logical ways to prepare your physical work space for a retreat, but a harder job, I think, is to focus on whatever retreat task you have set for yourself. Prepare for your retreat by walking around your home like a stranger, as if you have arrived at this haven just to enjoy a writing retreat. Arrange a chair before a window so you can watch birds; find a flower or tree or rock to identify. Turn a chair so your back is to the room.

My idea of the perfect retreat would include ordering meals from a personal chef to be delivered on my preferred schedule, but that is a fantasy. So I enjoy a bonus benefit available only to people who have partners: the retreat diet and exercise plan. When my partner isn’t here, I don’t cook as much, therefore I don’t eat as much, therefore I’m leaner and more focused. I often make a big batch of spaghetti or meat loaf, and eat similar meals for several days.

In my study, I look at each project I’ve begun to choose which one I’ll work on. I write notes so I’ll remember, when I’m ready to begin the other projects, what I was thinking, and put them firmly aside. Whether my writing is going well or not, it’s far too easy to sidestep into another writing project that looks more seductive. Even though I am my own boss and have set up my own schedule for writing, I dislike authority enough that my subconscious mind tries to flout it and sneak off to another fascinating story.

How it works: retreat reality

As soon as I got to my tidy office, I realized that in my haste to begin a retreat I’d forgotten that after days of travel and trouble, I needed to clear my journal. I’d recorded observations relating to several different writing projects, marking them with sticky notes in my journal so I could find them quickly. Each one needed to be placed it its proper file before I forgot the details.

As I recorded these notes, I recorded comments for the organizer of the meeting I’d attended, and sent those off— telling myself that while this was not a retreat activity, it was legitimate work as part of clearing my desk for writing.

During my lunch break, I referred to my journal and realized that I needed to revise my class presentation for Road Scholar on ranching in South Dakota. That’s creative, I thought, and it concerns on one of my usual writing topics, so it’s a legitimate retreat task. I completed the revision.

By then, I was distracted by the pain of an injury and called a doctor who agreed to see me that afternoon. The doctor was able to alleviate my pain but as I drove home I wondered if I had killed my retreat by leaving the house and breaking my concentration. Discouraged, I sat in my chair, read a few pages, and fell asleep.

Footsteps jerked me out of my nap. I stepped outside to find an insurance salesman on my deck, the first such caller in six years! Repeatedly and at length, I explained why I did not need additional insurance.

Now what? Nerves jangled, I turned to my calendar and my journal work list and realized I was obligated to attend a meeting the next afternoon, and had promised a friend to car-shop the day after that. My stomach knotted. I’d sabotaged myself by incomplete planning. Should I declare my retreat a failure?

No, I decided. The retreat was not over unless I allowed it to be.

First I had to recapture the feeling. If I allowed interruptions to make me angry, I was wasting my own time and becoming even more distracted. I had to dispose of disturbances efficiently, choosing which jobs I could complete and which I might postpone.

Part of my distraction, I realized, was having had a sketchy lunch; I had no enthusiasm for cooking, but discovered some attractive leftovers. I took my time arranging the meat, potatoes and gravy on the plate and heating them in the microwave while I made a salad. When I sat down to eat, I thought about my choices.

I was still alone in the house. I could recover from these setbacks. Instead of cancelling my private retreat, I decided, I would simply conduct a series of short retreats. I’d begin each day with a couple of cups of coffee in bed, dogs at my side. I’d write in my journal about my primary project: this essay about conducting my own retreat.

Next I planned a simple menu for several days, choosing ingredients on hand, because I knew my concentration would be broken if I was either hungry or constantly snacking.

During the morning before the meeting, I’d write as much as I could. After the meeting, I’d attend to online communication, putting off anything that could wait a day or two. The next day, I’d honor my morning commitment and then write in the afternoon.

The Petite Retreat

So began my week of discovering the concept of the miniature retreat, and I can recommend it. In fact, since many of us are convinced we don’t “have time” for a long retreat, perhaps learning how to conduct a retreat in a day or two, or even a couple of hours, might be considerably more useful to the average busy writer.

Before my afternoon meeting, I wrote notes and drafts of several ideas I’d recorded in my journal, so I was able to attend the meeting with a feeling of accomplishment that allowed me to be patient with the usual delays. Later, at the computer, I read a message from a writer who has been to Windbreak House on retreat. Her husband had just left for a ten-day trip and she had declared a personal retreat. She wrote, “I have the house to myself (it also means I have all the chores to myself, but leave that aside for the moment.)”

Before my afternoon meeting, I wrote notes and drafts of several ideas I’d recorded in my journal, so I was able to attend the meeting with a feeling of accomplishment that allowed me to be patient with the usual delays. Later, at the computer, I read a message from a writer who has been to Windbreak House on retreat. Her husband had just left for a ten-day trip and she had declared a personal retreat. She wrote, “I have the house to myself (it also means I have all the chores to myself, but leave that aside for the moment.)”

Serendipity! I thought. We’re both dedicated to our work and are conducting our own retreats; perhaps we can help each other.

“I seem to be getting over the gloom of separation anxiety,” she wrote, “and am moving into active embrace of the prospect of solitude. I will have some days that I have to go to town and work on projects at the rentals, but I will endeavor to keep the retreat spirit on the days when I’m home. I made a good start today by doing another revision pass and eating at odd hours.”

Again I was struck by the parallels; we both have obligations that keep us from shutting the world entirely out, and we both miss our spouses. I hadn’t thought to call it “separation anxiety,” but I was feeling the same. I don’t enjoy cooking for myself as much as cooking for someone else. When my partner is home, part of my morning journal time involves reviewing any available leftovers and deciding what to make for lunch and supper. Making preparations tells me when to begin both meals, and often keeps me from worrying about meals when I’m writing.

If I’d prepared properly for my own retreat, I would have frozen meals ready for quick preparation. Since I didn’t think ahead, don’t buy pre-packaged food, or live where I can get food delivered, I usually make a batch of one or two favorite meals that can be quickly reheated. My friend said she was surviving on hummus and potato salad and intended to plan ahead more effectively next time too.

Both of us are in a unique position in our homes, making retreats more workable. We both live some distance from town, so we don’t have the distractions of nearby traffic, and few neighbors drop by; we get few phone calls. (If your own home doesn’t lend itself to brief retreats, consider house-sitting.)

We agreed that the main obstacle to retreating into writing is mental. As she puts it,

“. . . making the commitment to yourself that you’re dedicating this time exclusively to writing (doing of, thinking about, reading about, etc.) . . .”

Her comment reminded me that a writing retreat requires more than writing; it includes reading and thinking about writing as well. I was also pleased to be reminded that this is the way real teaching and learning works: I offered her some of my suggestions, and her thinking inspired me: we both give, and we both take from the exchange.

The power of intention

My friend commented that making the decision to do the retreat was “weirdly wonderful,” that she, too, felt a huge release,

“. . . like I’d just gotten a massage. A marvelous lesson in the power of intention. I took an unseemly pleasure in defining my rules— monitoring email OK, responding unless absolutely necessary if a work project popped up was not. Checking weather OK, but no surfing. No TV. Doing dishes is OK, but only if you want to. Laundry is out of the question.”

Here we differed; my washer and dryer are just far enough from my desk to constitute a brain-clearing stroll with room to stretch, so I declared laundry to be OK that afternoon. With a load in the washer, I sent a few more messages and then found a reply from my retreating friend:

“Decided I ‘wanted’ to get the dishes cleaned up Wednesday evening, and the spell was broken. The motions of that disliked chore turned on the brain-churn of chores looming and the to-do list for town the next day. I still spent the evening reading and writing, but it did feel like the last night of retreat, processing the prospect of re-entry.”

“Brain-churn of chores”— that’s usually what wakes me up in the mornings if I allow it to. While waking for retreat, I’ve consciously pushed those thoughts away and concentrated my thinking on writing projects. During this rainy weather, I’ve forced myself to ignore the muddy paw-prints on the stairs and the dust in the corners; time enough to attend to those things when the rain stops.

What about those chores?

Still, everyone has daily jobs that, if we allow them to, can distract us from the kind of mood required for serious creative work. I can incorporate some jobs into a writing routine. When I come to a paragraph that baffles me, I may do dishes or defrost hamburger, slice vegetables or weed a flower bed while considering possibilities. None of those repetitive jobs can seriously distract a creative mind at work, though I have been known to burn rice when I rush downstairs to record a thought.

And some chores can be postponed. I’ll vacuum the house when my partner gets home and I’m distracted anyway. I’ll make a grocery list when he’s here to remind me of items I might forget. I’ll get the mail when I’m taking a break from writing.

My new challenge, then, was how to make my retreat work during short periods between the distracting obligations I’d discovered. I devised several methods and symbols to signal a new period of retreat.

How can I create tranquility?

If a retreat will be only a few hours or a day or two, it’s important to focus quickly, and learn to drop into retreat mode at will. I established signals to remind myself to avoid confusion and concentrate on the purpose of my retreat.

When I sat down to work on my journal at the dining room table, I pushed my nose deep into the bowl of lilacs and inhaled, letting the light, silky scent remind me to inhale and hold my breath, exhaling slowly.

Walking the dogs became part of my ritual when I needed to change mental gears. After I completed a job, whether it was an interruption to my writing or a writing draft, I changed my mood by taking the dogs outside to play or walk while I stretched and did bends.

Wildflowers as well as cultivated plants surround my home, but I usually notice them only when I’m working at gardening. For the retreat atmosphere, therefore, I took time to appreciate my surroundings as if I were in an exotic jungle. I sat on a railroad tie fence and watched a tree swallow swoop to collect a bug. I crawled through the grass looking for bluebells, found a smooth black rock and placed it in the precise center of a bowl worn in a sandstone rock. When one Westie brought me a baby robin carried gently in his mouth, I climbed a tree and put it back in the nest.

Wildflowers as well as cultivated plants surround my home, but I usually notice them only when I’m working at gardening. For the retreat atmosphere, therefore, I took time to appreciate my surroundings as if I were in an exotic jungle. I sat on a railroad tie fence and watched a tree swallow swoop to collect a bug. I crawled through the grass looking for bluebells, found a smooth black rock and placed it in the precise center of a bowl worn in a sandstone rock. When one Westie brought me a baby robin carried gently in his mouth, I climbed a tree and put it back in the nest.

Concentrating on the details of my surroundings refreshed me. Arranging a few stems of Sweet William in a vase in the bathroom did not break my concentration, but shifted my focus. During these times of not-writing, aspects of the writing I was doing floated to the surface of my mind.

Think instead of talking

Having no other people in my house encouraged my uninterrupted thinking. I didn’t have to consider anyone else’s feelings, or respond to questions; providing attention to the dogs didn’t require much thought. I could walk with them, watch them hunt voles and run in circles, and throw their toys, all while relaxing and clearing my brain, or struggling with a knotty writing problem.

Think about it: responding to human interruptions can take considerable time in part because we observe social conventions; we’re polite, we explain, we listen, we justify. But if the telephone rings and I don’t answer it, time is saved. If someone posts to my timeline on Facebook and I don’t see it, my work is not interrupted. The choice is mine; the person calling or posting doesn’t know what I’m doing and will be happy when I do respond. Ignoring online distractions was similar to being alone in the house, without the necessity to respond to conversation.

Reading as writing

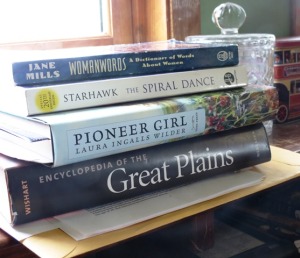

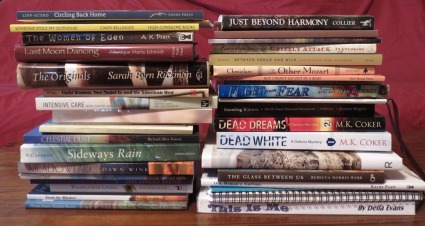

Sometimes I get so caught up in daily chores and writing that I may let significant articles and books that might inspire and inform my writing stack up beside my reading chair. I scan them distractedly while waiting for a soup to simmer or a conversation to be finished. So concentrated reading on the subjects I write most about became part of my retreat. Having given myself permission to read in the daytime, I slashed like a lawnmower through stacks of magazines and books that had gathered dust for months. Instead of reading my usual relaxing mysteries at night, I read serious stuff and took notes for future writing and talks. Because I was working later than usual, I also felt better about any diversions that occurred during the day.

Sometimes I get so caught up in daily chores and writing that I may let significant articles and books that might inspire and inform my writing stack up beside my reading chair. I scan them distractedly while waiting for a soup to simmer or a conversation to be finished. So concentrated reading on the subjects I write most about became part of my retreat. Having given myself permission to read in the daytime, I slashed like a lawnmower through stacks of magazines and books that had gathered dust for months. Instead of reading my usual relaxing mysteries at night, I read serious stuff and took notes for future writing and talks. Because I was working later than usual, I also felt better about any diversions that occurred during the day.

My retreat rules banned reading that was not on a topic related to my work. I was delighted when my friend on retreat said one morning that she’d “allowed” herself to read my note to her about our retreats only when she was on a break.

Meanwhile, she reported that her first mini-retreat was two days long: “an intense writing day, followed by an evening devoted to reading about writing and to writing in my journal about the reading and about the projects I’m working on. The next day was more writing, more reading.” She was exhausted, but “maintained internet/media limits and spent another quiet evening reading.” All this worked, she added, because she had the house to herself.

I, too, was feeling more satisfied with my small retreats of a morning and then an afternoon, and I wasn’t as exhausted because I hadn’t been able to immerse myself as fully as she had. I had, though, done what I could with the time I had and that was a source of satisfaction.

The retreat attitude

So how is a series of mini-retreats different from a normal work week? And how can we create the energy and the focus of a retreat in a shorter period?

I believe the power of my intent and the attitude I establish toward my work can allow me to conduct a useful retreat, even if it’s brief. During a normal day, my focus is outward: on my partner, on how our mutual day evolves, and on the obligations we have to one another. When he’s gone, I shift my attention to his evening call, leaving the rest of the day free for me to focus on my work. Reminding myself that my primary intention is my writing, I can allow other concerns to become invisible.

A danger zone is the restless periods between bouts of writing. When I get up to go to the bathroom, or fix a meal, or just stretch, I must resist the temptation to go online or check my phone. While the tasks of house-keeping like laundry or dishes don’t automatically pull my mind away from deeper thinking, the mindless chatter of the internet does.

This retreat also reminded me, and my writing friend, of another important element of a successful retreat of any length: reading books instead of the internet ether.

She puts it best:

“The focus on hard copy reading reveals how shallow and unsatisfying most of what’s available on the internet appears. . . . It’s easy to justify the surfing by telling yourself that you’re ‘staying informed’ by looking at news or literary sites, but that kind of reading does not allow for the slow reflection one achieves by turning pages and making notes in the margin.”

Moreover, because I have made time, I have the luxury of time to sit and stare at a smooth stone held in my hand and see how my mind will connect that stone, the sun on my back, the birdsong, with my writing. I can watch the cattle moving across the gully below the house, enjoying the way they kick up their heels. I can sit on the deck listening to the birds without checking my watch.

On each day of my retreat since, I have begun the day by planning what it will contain, including obligations to others that I can’t escape. I figure out what to have for lunch. Then I note the times in the day that I can consider retreat time, and note which project I’ll tackle. I can breathe deeply, knowing exactly when I’ll be on retreat, and what I have to do before that time.

My friend remarks that she is learning to make peace with how slowly writing can develop, and getting better at focusing when she has the time to do so. I agree. Once I have established writing time and know that I will keep it, I can be attentive at a meeting, hold conversations, answer email, and vacuum, throwing all my energy into what I am doing at that moment.

When my writing time seems brief, I remind myself that Graham Green created a writing schedule of two hours a day. He was so strict about stopping after exactly two hours that he sometimes didn’t finish a sentence. But at that pace he published 26 novels, as well as many short stories, plays, screenplays, memoirs, and travel books.

Linda M. Hasselstrom

Windbreak House

Hermosa, South Dakota

© 2015, Linda M. Hasselstrom

# # #

If a writer asks me to decide whether to continue writing or give up, I always refuse; no one can judge how much help the act of writing might provide to an individual, even if no single word ever appears in print. I will help a writer improve her work, and suggest possibilities for publishing, but no one can guarantee publication or declare that it is impossible. I remind them that my opinion may not be correct, but I’ve been able to appreciate something in the work of every writer with whom I’ve worked.

If a writer asks me to decide whether to continue writing or give up, I always refuse; no one can judge how much help the act of writing might provide to an individual, even if no single word ever appears in print. I will help a writer improve her work, and suggest possibilities for publishing, but no one can guarantee publication or declare that it is impossible. I remind them that my opinion may not be correct, but I’ve been able to appreciate something in the work of every writer with whom I’ve worked. My method is simple. I ask each writer to send to me in advance the writing that they want to work on during the retreat. Now that it’s possible, I prefer this writing be sent electronically, so that I can download it to a flash drive. Then I carefully read each submission several times, writing my comments right in the manuscript.

My method is simple. I ask each writer to send to me in advance the writing that they want to work on during the retreat. Now that it’s possible, I prefer this writing be sent electronically, so that I can download it to a flash drive. Then I carefully read each submission several times, writing my comments right in the manuscript. sank from view.” Then I attach to the writer’s manuscript my handout on dangling modifiers, already prepared with examples of the error and how to correct it. By providing this additional information, I’m offering the writer an opportunity to learn enough about the error to avoid it in future writing: as if we’d had a full class on dangling modifiers.

sank from view.” Then I attach to the writer’s manuscript my handout on dangling modifiers, already prepared with examples of the error and how to correct it. By providing this additional information, I’m offering the writer an opportunity to learn enough about the error to avoid it in future writing: as if we’d had a full class on dangling modifiers. One of my most useful writing tools has been my journal, and I believe strongly in the power of journaling to aid self-discovery. Write fiercely in your journal, I say, write recklessly. Do not let your inner editor slow you down. Do not channel that English teacher in high school who always found an error. Don’t think about spelling or grammar or how this will look in print. Emote. Stomp through the words. Fling handfuls of syllables in the air and let them land on your paper. Often the heat of the anger or the pain of the loss or the joy of the new love will inspire the perfectly correct words that will never emerge if you think “someone is going to read this.” Journals must be private; no one should read your journal any more than a stranger can pry open your brain and look inside. Your journal is your freedom, your inspiration, your guide, and ultimately your resource.

One of my most useful writing tools has been my journal, and I believe strongly in the power of journaling to aid self-discovery. Write fiercely in your journal, I say, write recklessly. Do not let your inner editor slow you down. Do not channel that English teacher in high school who always found an error. Don’t think about spelling or grammar or how this will look in print. Emote. Stomp through the words. Fling handfuls of syllables in the air and let them land on your paper. Often the heat of the anger or the pain of the loss or the joy of the new love will inspire the perfectly correct words that will never emerge if you think “someone is going to read this.” Journals must be private; no one should read your journal any more than a stranger can pry open your brain and look inside. Your journal is your freedom, your inspiration, your guide, and ultimately your resource. My family would have me committed if they knew that I drove 6 hours from my mother’s to sit on a hill and write. . . . what they don’t understand is that I needed Linda and [another writer at the retreat] to reinforce and to encourage me. I needed to be away from the noise of my family. . . . On the hill, for the first time ever, I wrote about what used to be a taboo topic.

My family would have me committed if they knew that I drove 6 hours from my mother’s to sit on a hill and write. . . . what they don’t understand is that I needed Linda and [another writer at the retreat] to reinforce and to encourage me. I needed to be away from the noise of my family. . . . On the hill, for the first time ever, I wrote about what used to be a taboo topic.

Writing is not the only art celebrated and practiced here. One woman played her guitar in the living room after supper, inviting a singalong. A writer who had studied the Japanese art of ikebana created an arrangement of stones, grandmother cedar, a weathered plank, juniper, native stone and grasses that symbolized her experience at the retreat, and brought peaceful symmetry to the house for months. Other guests, unfamiliar with the art, moved it from one room to another, wrote about it, photographed and studied it. One man wrote a postcard to the creator, expressing his astonishment and delight at finding the ikebana in his room. I mailed it for him since I felt it would be unethical to reveal her address.

Writing is not the only art celebrated and practiced here. One woman played her guitar in the living room after supper, inviting a singalong. A writer who had studied the Japanese art of ikebana created an arrangement of stones, grandmother cedar, a weathered plank, juniper, native stone and grasses that symbolized her experience at the retreat, and brought peaceful symmetry to the house for months. Other guests, unfamiliar with the art, moved it from one room to another, wrote about it, photographed and studied it. One man wrote a postcard to the creator, expressing his astonishment and delight at finding the ikebana in his room. I mailed it for him since I felt it would be unethical to reveal her address. For the record, vegetarians are welcome in this beef-raising haven, though I do not care for the smell of boiling carrageen moss. My acceptance of writers to work here is based solely on their writing, and whether I believe I can help them, not on their profession or anything else I might know about them.

For the record, vegetarians are welcome in this beef-raising haven, though I do not care for the smell of boiling carrageen moss. My acceptance of writers to work here is based solely on their writing, and whether I believe I can help them, not on their profession or anything else I might know about them. Most writers attend alone, or in clusters of two or three, but group retreats have included graduate students and teachers from various universities who brought tents so that the guests who couldn’t fit into the house could camp among the trees. During their stay they hiked in the Black Hills and I talked about writing and responsible cattle ranching on the shortgrass prairie.

Most writers attend alone, or in clusters of two or three, but group retreats have included graduate students and teachers from various universities who brought tents so that the guests who couldn’t fit into the house could camp among the trees. During their stay they hiked in the Black Hills and I talked about writing and responsible cattle ranching on the shortgrass prairie.

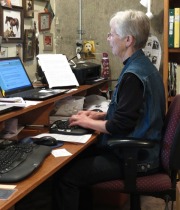

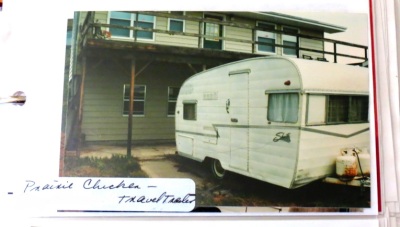

Once, when a fire in the forested hills poured smoke and ashes down on Tamara’s house during a retreat, she took refuge in the travel trailer with her German shepherd. I was startled awake by a deep “WOOF!” at sunrise.

Once, when a fire in the forested hills poured smoke and ashes down on Tamara’s house during a retreat, she took refuge in the travel trailer with her German shepherd. I was startled awake by a deep “WOOF!” at sunrise. Once a writer walked up the retreat house steps carrying mounted head of a buck deer. On her way to the retreat she’d been touring a second-hand store, she said, and he looked lonely, so she brought him along; she named him Timothy, and he supervised her writing week. She later said that when she was stopped for speeding on the way home, she thought the sight of Timothy in the passenger seat meant the difference between a ticket and the warning she got.

Once a writer walked up the retreat house steps carrying mounted head of a buck deer. On her way to the retreat she’d been touring a second-hand store, she said, and he looked lonely, so she brought him along; she named him Timothy, and he supervised her writing week. She later said that when she was stopped for speeding on the way home, she thought the sight of Timothy in the passenger seat meant the difference between a ticket and the warning she got.

One retreat writer sent me a quilt made by her mother. We use it regularly in Eagle, and she assured us that it’s durable, so if we wear it out, she’d send another. Other quilters have given the retreat house decorative hangings inspired by their time here.

One retreat writer sent me a quilt made by her mother. We use it regularly in Eagle, and she assured us that it’s durable, so if we wear it out, she’d send another. Other quilters have given the retreat house decorative hangings inspired by their time here. Another writer had bought a batch of quilt pieces in a second-hand store on her way to retreat, and enjoyed having space enough to lay them out on the floor to see their pattern, as preparation for writing about them.

Another writer had bought a batch of quilt pieces in a second-hand store on her way to retreat, and enjoyed having space enough to lay them out on the floor to see their pattern, as preparation for writing about them.

We also have a Blizzard Policy; if a blizzard is severe enough that the writer can’t drive to the highway, or the highways are closed, all the days during which you can’t leave are without charge. If the writer didn’t bring enough food, my freezers are always full. Several writers tell me they now watch weather reports, hoping to schedule retreats during a major winter storm.

We also have a Blizzard Policy; if a blizzard is severe enough that the writer can’t drive to the highway, or the highways are closed, all the days during which you can’t leave are without charge. If the writer didn’t bring enough food, my freezers are always full. Several writers tell me they now watch weather reports, hoping to schedule retreats during a major winter storm. At first, I envisioned the retreat as being so harmonious that I would not need to set rules. Each group of guests, I supposed, would decide the mood of the retreat among themselves. Civilized women shouldn’t need a handbook or a set of Dos and Don’ts. Surely, I thought, the women who came to a writing retreat would be experienced at publishing, needing only a quiet place and some gentle guidance to turn out page after page of brilliant writing.

At first, I envisioned the retreat as being so harmonious that I would not need to set rules. Each group of guests, I supposed, would decide the mood of the retreat among themselves. Civilized women shouldn’t need a handbook or a set of Dos and Don’ts. Surely, I thought, the women who came to a writing retreat would be experienced at publishing, needing only a quiet place and some gentle guidance to turn out page after page of brilliant writing. The house has no rule of silence, but I encourage respectful quiet, suggesting that residents turn off their phones. If they are worried about emergencies, I tell them how their loved ones can reach the local Sheriff if they need to contact us. Some just check their messages once a day and do not respond. Once in a while a writer uses a smart phone to go online, but the retreat house has no internet connection. Getting disconnected from these daily distractions can make a huge difference in a writer’s life, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for some; a few have been astonished that I’d even suggest it. Most are later grateful.

The house has no rule of silence, but I encourage respectful quiet, suggesting that residents turn off their phones. If they are worried about emergencies, I tell them how their loved ones can reach the local Sheriff if they need to contact us. Some just check their messages once a day and do not respond. Once in a while a writer uses a smart phone to go online, but the retreat house has no internet connection. Getting disconnected from these daily distractions can make a huge difference in a writer’s life, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for some; a few have been astonished that I’d even suggest it. Most are later grateful. When I have an idea, it’s easy to write furiously: I take notes in my journal, I mumble to myself and take more notes while walking the dogs, and I sit at the computer and type wildly. Once I’m immersed in a project, my subconscious mind keeps working while I get lunch started, answer an email or two. At night, in order to stop thinking about the writing, I read a mystery until I fall asleep.

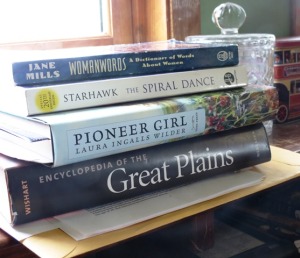

When I have an idea, it’s easy to write furiously: I take notes in my journal, I mumble to myself and take more notes while walking the dogs, and I sit at the computer and type wildly. Once I’m immersed in a project, my subconscious mind keeps working while I get lunch started, answer an email or two. At night, in order to stop thinking about the writing, I read a mystery until I fall asleep. As soon as I’d made the decision to turn my ranch house into a writing retreat, I started coming back to the ranch more often to help my assistant, Tamara, get ready to make the plan a reality. She provided unlimited energy and creative ideas, as well as hard labor. She recalls “mowing the huge yard (and the wonderful varied odors as I cut the different plants that had been baking in the sun), painting the rooms, putting weatherproofing stain on the deck.”

As soon as I’d made the decision to turn my ranch house into a writing retreat, I started coming back to the ranch more often to help my assistant, Tamara, get ready to make the plan a reality. She provided unlimited energy and creative ideas, as well as hard labor. She recalls “mowing the huge yard (and the wonderful varied odors as I cut the different plants that had been baking in the sun), painting the rooms, putting weatherproofing stain on the deck.” Analyzing my one-family house for its suitability as a retreat, we decided that visiting writers would occupy the main floor, sharing the kitchen, dining room, living room and bathroom. We named the master bedroom Eagle in honor of a Daniel Long Soldier painting. A smaller bedroom became Dragonfly after a colorful print. My study was already established in the walk-out basement, abutted by a half-bath with its walls lined with bookshelves. I created a single bed by putting a door across two antique trunks and adding a foam mattress. Tam dubbed the place Burrowing Owl after my favorite prairie owl, which lives in old prairie dog burrows.

Analyzing my one-family house for its suitability as a retreat, we decided that visiting writers would occupy the main floor, sharing the kitchen, dining room, living room and bathroom. We named the master bedroom Eagle in honor of a Daniel Long Soldier painting. A smaller bedroom became Dragonfly after a colorful print. My study was already established in the walk-out basement, abutted by a half-bath with its walls lined with bookshelves. I created a single bed by putting a door across two antique trunks and adding a foam mattress. Tam dubbed the place Burrowing Owl after my favorite prairie owl, which lives in old prairie dog burrows.

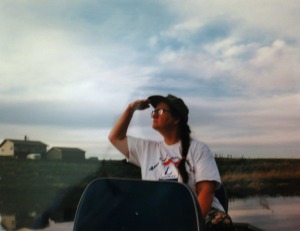

“Land ho!” shouted Barbara, posing with one hand shading her eyes, scanning the horizon.

“Land ho!” shouted Barbara, posing with one hand shading her eyes, scanning the horizon. As we neared shore, Barbara alerted me to the sound of chorus frogs. I’d been hearing them all during that wet spring of 1997, but had never seen them.

As we neared shore, Barbara alerted me to the sound of chorus frogs. I’d been hearing them all during that wet spring of 1997, but had never seen them. Mystery writer M.K. Coker came to Windbreak House Retreats for a solitary retreat in October, finishing the next book in the terrific Dakota Mystery series in time for a November deadline. This report about the experience (printed with M.K.’s permission) ought to encourage every single writer: 1,000 words on the day of arrival!

Mystery writer M.K. Coker came to Windbreak House Retreats for a solitary retreat in October, finishing the next book in the terrific Dakota Mystery series in time for a November deadline. This report about the experience (printed with M.K.’s permission) ought to encourage every single writer: 1,000 words on the day of arrival!

And in March of 2017, look for number six: Dead Hot.

And in March of 2017, look for number six: Dead Hot. Face facts; moving your physical body to an “official” retreat won’t make you a writer. I once studied the Shaolin Kung Fu five-animal system, concentrating on the form known as “White Crane.” My instructor worked with me on several aspects of this martial art, developing my breath control and balance, speed and timing. Gradually, I developed strength and flexibility while learning fighting stances based on the symmetry and stability of a crane’s movements. Eventually, I understood how to use my hands and arms as weapons, learned the backfist and claw hand, and how to deliver the blade kick to an attacker’s knee. Throughout my training, my instructor emphasized that physical abilities alone would not enable me to master the form; meditation and focus are key aspects of the martial arts. In the end, I was not willing to devote three or more hours a day to practicing Karate in order to master its nuances on the chance I would use my skill to repel an attacker.

Face facts; moving your physical body to an “official” retreat won’t make you a writer. I once studied the Shaolin Kung Fu five-animal system, concentrating on the form known as “White Crane.” My instructor worked with me on several aspects of this martial art, developing my breath control and balance, speed and timing. Gradually, I developed strength and flexibility while learning fighting stances based on the symmetry and stability of a crane’s movements. Eventually, I understood how to use my hands and arms as weapons, learned the backfist and claw hand, and how to deliver the blade kick to an attacker’s knee. Throughout my training, my instructor emphasized that physical abilities alone would not enable me to master the form; meditation and focus are key aspects of the martial arts. In the end, I was not willing to devote three or more hours a day to practicing Karate in order to master its nuances on the chance I would use my skill to repel an attacker. Examine your home, inside and out, for nooks that might become secret retreat spots even in a busy day: the attic is particularly tempting, especially if access is via a folding ladder you can pull up after you. Shut yourself into a spare bedroom at the back of the house. One writer I know hides in a vine-covered alcove in her back yard; she’s out of sight from the sidewalk six feet away, and unable to hear telephones or raps at the door. Her lack of electricity is outweighed by the privacy. Draw the mental curtains and you’ll feel as if you’re a motel guest, free to set your own schedule.

Examine your home, inside and out, for nooks that might become secret retreat spots even in a busy day: the attic is particularly tempting, especially if access is via a folding ladder you can pull up after you. Shut yourself into a spare bedroom at the back of the house. One writer I know hides in a vine-covered alcove in her back yard; she’s out of sight from the sidewalk six feet away, and unable to hear telephones or raps at the door. Her lack of electricity is outweighed by the privacy. Draw the mental curtains and you’ll feel as if you’re a motel guest, free to set your own schedule.

A real retreat furnishes special effects, but you can duplicate some of these at home. My perfect retreat was surrounded by wooded hillsides where I often walked with my dog and the house hound. One day, I noticed a tangle of wild grape vines and selected three brilliant red stems to display in the empty green bottle I’d found on my last walk. My former country home and my new city home are both surrounded by wildflowers I’ve planted, but I seldom stop writing to pick nosegays. Arranging the grape vines beside a whitened jaw bone on the broad window ledge before my desk did not break my concentration on a knotty problem in the essay I was writing, but the bouquet brightened other hours at my computer. These days, remembering the joy of arranging that window sill scene, I’m more likely to take a refreshing walk among my flowers without losing concentration on the day’s writing job.

A real retreat furnishes special effects, but you can duplicate some of these at home. My perfect retreat was surrounded by wooded hillsides where I often walked with my dog and the house hound. One day, I noticed a tangle of wild grape vines and selected three brilliant red stems to display in the empty green bottle I’d found on my last walk. My former country home and my new city home are both surrounded by wildflowers I’ve planted, but I seldom stop writing to pick nosegays. Arranging the grape vines beside a whitened jaw bone on the broad window ledge before my desk did not break my concentration on a knotty problem in the essay I was writing, but the bouquet brightened other hours at my computer. These days, remembering the joy of arranging that window sill scene, I’m more likely to take a refreshing walk among my flowers without losing concentration on the day’s writing job. You’ve gone online to look at the websites of writing retreats from Maine to Malibu, from Switzerland to Saskatchewan, fantasizing about having a massage after a hard writing session, then relishing a catered lunch, followed by a nap, a glass of wine, and a stimulating discussion with other writers.

You’ve gone online to look at the websites of writing retreats from Maine to Malibu, from Switzerland to Saskatchewan, fantasizing about having a massage after a hard writing session, then relishing a catered lunch, followed by a nap, a glass of wine, and a stimulating discussion with other writers. Do you want company? Group retreats can be beneficial; having two or three thoughtful writers looking at your work means you’re likely to get more suggestions for improvement. Before you ask people you know, however, ask yourself if you’ll work well together, or visit more than you write. Also, each additional person reduces the time I have to spend with you.

Do you want company? Group retreats can be beneficial; having two or three thoughtful writers looking at your work means you’re likely to get more suggestions for improvement. Before you ask people you know, however, ask yourself if you’ll work well together, or visit more than you write. Also, each additional person reduces the time I have to spend with you. Decide what you want to accomplish: finish that short story? Complete a rough draft of an essay? Arrange poems for book publication? Record your goals in your journal, and assess the plan at the end of each day of your retreat, so you can ask me to make changes in our schedule if necessary.

Decide what you want to accomplish: finish that short story? Complete a rough draft of an essay? Arrange poems for book publication? Record your goals in your journal, and assess the plan at the end of each day of your retreat, so you can ask me to make changes in our schedule if necessary. Once you’ve chosen a writing project and set goals for your retreat, turn your attention to the third, and probably most complicated aspect of preparing for your stay: what to take with you. For several days, as you move through your normal schedule, make lists of what you normally use that you will need at retreat. Will you sleep better with your own pillow? Some writers have brought comforting stuffed animals to help them relax—but no live ones, please.

Once you’ve chosen a writing project and set goals for your retreat, turn your attention to the third, and probably most complicated aspect of preparing for your stay: what to take with you. For several days, as you move through your normal schedule, make lists of what you normally use that you will need at retreat. Will you sleep better with your own pillow? Some writers have brought comforting stuffed animals to help them relax—but no live ones, please. What writing materials do you need? Include whatever you use most: laptop and all necessary chargers and electronic paraphernalia. I will put your writing on a flash drive so I can use my printer to produce copies for both of us, but if you want to print your own copies, bring a printer, ink cartridges, paper, cords. Bring your journal and the kind of notebook you prefer, favorite books. Windbreak House has extra supplies of pens and pencils along with the usual office supplies like paperclips, rubber bands, erasers, Kleenex, and scotch tape. Again, if you forgot an essential item, I may be able to supply it.

What writing materials do you need? Include whatever you use most: laptop and all necessary chargers and electronic paraphernalia. I will put your writing on a flash drive so I can use my printer to produce copies for both of us, but if you want to print your own copies, bring a printer, ink cartridges, paper, cords. Bring your journal and the kind of notebook you prefer, favorite books. Windbreak House has extra supplies of pens and pencils along with the usual office supplies like paperclips, rubber bands, erasers, Kleenex, and scotch tape. Again, if you forgot an essential item, I may be able to supply it. Don’t forget that you will be using extra energy (remember studying for finals?), so bring plenty of healthy, and probably a few unhealthy, snacks. Do you have a favorite brand of coffee or tea, milk, fruit or vegetable juices or other beverages? You’ll be amazed at how much nibbling you can do while thinking about characters or commas. If you enjoy a glass of wine or a drink in the evening, bring what you need. And remember the advice of poet William Stafford: “Don’t write when you’ve been drinking, but if you do, don’t take it too seriously.”

Don’t forget that you will be using extra energy (remember studying for finals?), so bring plenty of healthy, and probably a few unhealthy, snacks. Do you have a favorite brand of coffee or tea, milk, fruit or vegetable juices or other beverages? You’ll be amazed at how much nibbling you can do while thinking about characters or commas. If you enjoy a glass of wine or a drink in the evening, bring what you need. And remember the advice of poet William Stafford: “Don’t write when you’ve been drinking, but if you do, don’t take it too seriously.” Of course you are an essential part of the lives of your family and friends, but your retreat is intended to benefit your writing by getting you away from these loving distractions. The people who care about you want you to succeed, so you need to organize events at home to minimize or prevent distractions from your work. Few people these days travel without a phone, and I don’t expect you to leave it behind, but try to behave as though you have. Notify friends and business associates that you are out of reach; feel free to tell them retreat rules prohibit phone calls and Internet connection.

Of course you are an essential part of the lives of your family and friends, but your retreat is intended to benefit your writing by getting you away from these loving distractions. The people who care about you want you to succeed, so you need to organize events at home to minimize or prevent distractions from your work. Few people these days travel without a phone, and I don’t expect you to leave it behind, but try to behave as though you have. Notify friends and business associates that you are out of reach; feel free to tell them retreat rules prohibit phone calls and Internet connection.

Here’s what you need to do on retreat: write, sleep, think, eat, write, think, walk, write, listen to comments on your writing, think while walking, sleep, write, eat while thinking, and repeat.

Here’s what you need to do on retreat: write, sleep, think, eat, write, think, walk, write, listen to comments on your writing, think while walking, sleep, write, eat while thinking, and repeat.

Before you leave the retreat, we will consider how you can establish a writing place and time at home. I’ll suggest ways to stay focused, and to begin your new program before you, or those voices of guilt, can talk you out of it. Don’t plan to get up in the dark and write for three hours before breakfast; find a time that will really work for writing, even if it’s only fifteen minutes a day. Then gently, but firmly, establish this time as yours. I’ve heard that one writer has instructed her children that only if the blood is spurting, indicating a severed artery and not merely a blood vessel, are they to bother her while she’s writing.

Before you leave the retreat, we will consider how you can establish a writing place and time at home. I’ll suggest ways to stay focused, and to begin your new program before you, or those voices of guilt, can talk you out of it. Don’t plan to get up in the dark and write for three hours before breakfast; find a time that will really work for writing, even if it’s only fifteen minutes a day. Then gently, but firmly, establish this time as yours. I’ve heard that one writer has instructed her children that only if the blood is spurting, indicating a severed artery and not merely a blood vessel, are they to bother her while she’s writing.