At 4:45 am, the first sounds I hear awakening are low murmuring chirps. When I open my eyes, the room is hazy gray with first light before sunrise. A breeze sighs through the open windows. I close my eyes, pat the dog, and snuggle deeper into the covers.

A vehicle whines over the hill on the highway, tires thumping as the driver accidentally veers into the rumble strips. I open my eyes and look toward the west windows. Over the deep blue Black Hills, a wispy cirrus cloud turns pink, reflecting the coming sunrise. While I dress, I look out the west windows at the blackbirds stomping through the tall grass, beaks stabbing as they gobble insects. The redwing blackbirds may be my favorite prairie birds. I love the bright audacity of their red and yellow epaulets in our tawny, grassy world, and their melodious songs.

Near a south window, a young robin lands on the deck railing and squawks.

The demanding youngster is one of three that fledged a day or two ago. I know that, under the deck, another pair of robins has built a nest six joists over from the first, and furnished it with three eggs the color of the sky. One of these robins zings out from under the deck just as an adult arrives, beak carrying a wiggly worm to feed the loud teenager. Apparently one set of parents are still taking care of the food bills while another is looking forward to the hatch.

Looking to the south, I see that the water held behind the small dam is sprouting a layer of water weeds. The dam was incorrectly built, so that no seal was created on the bottom of the pond. Even if it fills early in spring, the water leaks so steadily that before summer it is dangerous for cattle, who could become stuck in the soggy gumbo. When I mentioned to a neighbor that we jokingly call the pond Lake Linda, she said, “Oh, you mean the mud hole?”

But today the dark water ripples in the breeze. On the edge stands a Great Blue heron, hunched so that it resembles a cloaked and brooding figure out of the mythical East. While I eat breakfast, I periodically go to the window to look at the heron, hoping to see it stalking through the shallow water, hunting. Sometimes it stands immobile for long minutes, head tilted as it waits for prey. Then the great beak stabs down. The heron throws its head back and I might see a quick wriggling flash as it swallows a fish or frog. Gulp. The bird shakes itself, and begins to prowl again.

When we first spotted a heron here, several years ago, neither of us believed it could possibly be a Great Blue. But the bird’s size, and the long feathers trailing behind its head sent us to our bird identification guides. And when we saw it fly—lifting off with the great wings, tucking its neck into an S-shape, incredibly graceful and imposing—we had no doubt.

A long tongue of nearly stagnant water reaches into a gully in the hayfield, and a bulky bird, bright white and shoe-polish brown, squats at the gravelly edge. Through the binoculars, we can see its head is green, and it seems to be poking its long bill deep into the water. Though a dozen ordinary mallard ducks float on the pond or parade its edges, this bird is new to us; so far as we know, we’ve never seen it before. With help from various authorities, we discover it’s a Northern Shoveler, another long-distance migrant from Europe which has become Americanized.

Whoosh! A blackbird rockets past the window, and I realize that to the birds, this house is just a lump, an obstacle that keeps them from flying straight from one spot to another.

The grass in the yard outside the basement door parts and I recognize from its bright bronzy back and tail feathers that it’s a brown thrasher. Suddenly it leaps into the air and zooms into one of the cedars on the south side of the yard.

I wish I could identify birds by sound the way real “birders” do. The first time I hosted a group of these folks at the retreat house, I expected them to be wearing sturdy boots and binoculars strung around their necks. Surely they would fan out over the prairie, striding and stalking the resident birds.

Instead, they all got comfortable and started listening. They explained that they seldom SEE the birds they list in their identifications. They hear them, and that’s proof enough. I’ll never be a successful birder; I want to see the birds!

The next sound I hear is a hooting vibration of high notes; I know it is not a call, but it is evidence that a particular bird is flying near. The winnowing snipe has a rather ordinary chirp, but its distinctive, haunting sound is created by its flight: looping and soaring through the air. This remarkable bird can also swallow prey like small crustaceans and insects without pulling its long, flexible beak from the soil.

On the south side of the deck, a small table sits upside down over a floor mat: the protection we have devised for the robins’ nests. One spring several years ago, through a crack in the deck, I saw a robin sitting on the nest with a cape of snow over its back. We put the welcome mat over the area, and upended the table to hold it down. Now we provide the cover every year, moving it from nest to nest as families grow and depart.

Below the deck, on the south side of the yard, a tree swallow emerges from a tiny house Jerry built hoping to attract bluebirds. The sleek bird perches on a post and begins to preen itself. One spring, after we’d seen bluebirds clinging to electric wires in a snowstorm, Jerry built the nest boxes and installed them on the north and south sides of the house. A pair of bluebirds dropped by the next spring. The smaller one went inside, emerged a few minutes later, and they flew away. Apparently the home was not up to her standards.

Soon after, a pair of tree swallows arrived, their backs glowing blueblack in the sun. Both inspected the quarters on the north and moved right in. Almost the next day, another pair occupied the southern mansion. We haven’t seen the bluebirds since, but the tree swallows are so active and so graceful, we don’t mind.

When we sit under the deck in the evening, we have plenty of activity to watch as we listen to the surprising range of sound the birds display as they communicate.

Besides the robins’ singing and the tree swallows bickering before whizzing to forage for food, we often entertain other visitors. In years past, the barn was occupied every spring by barn swallows who built their mud nests under the eaves.

In the grove of trees, mourning doves lived, cooing softly and harmoniously all day.

Then the collared doves arrived, invasive birds with cawing voices and the nasty habit of driving out native species all over the world. Our mourning doves vanished, and now the collared doves arrive every spring.

The barn swallows have moved inside the roof of a loafing shed, and to the eaves of several other ranch buildings. I noticed fresh mud on the porch of the Writing Retreat house yesterday, and discovered one courageous pair has built a nest in the roof, a fine shelter, but besides mud and feathers, the porch will now be festooned with bird droppings.

As we read and sip our drinks under the deck, we comment on how tall the bachelor buttons are, and wonder when the Maltese cross will bloom. For a month, we’ve been eating radishes from tiny plots scattered among the tomatoes, peppers, and flowers. No matter what we’re discussing or reading, though, we’re always happy to watch the evening ballet of the barn swallows. I suppose they are flying for exercise and entertainment, but they always seem to visit us, gliding under the deck only a foot or two above our heads, sailing around the deck posts and between the house, garage, and greenhouse, chirping madly. Sunlight glows on their russet breasts; their pointed wings, curved like tiny scimitars, slice the air. Yesterday, as I drove my car up the slope toward the house, one barn swallow flew straight at my windshield as though it was going to attack the monster, veering overhead at the last possible second.

Prairie birds, all of these. Surely I’ve missed some that are familiar to other folks, or in other parts of the Great Plains. Look around; they may be where you are.

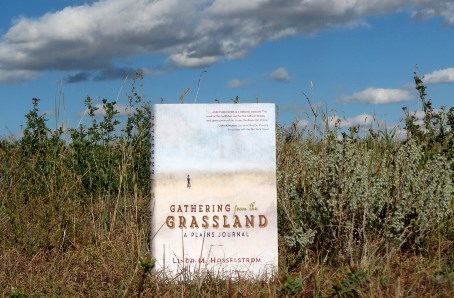

Linda M. Hasselstrom

Windbreak House

Hermosa, South Dakota

© 2023, Linda M. Hasselstrom

# # #

Some of these bird comments originally appeared on my Facebook page in June of 2020, before my husband, Jerry, died in an automobile accident. When I chose to post this for the summer solstice, I decided it would be too awkward to edit all the references to “we” into “I.”

Nearly all the bird photos were taken at my ranch, most using a telephoto lens, with the exception of the snipe photo (from iStock) and brown thrasher photo (from Public Domain).

Besides all these potential lights, I have lights on tall poles outside my house and my retreat house. These lights operate with a switch from inside the house, or with a device I can carry. I have to turn them on. When someone drives up, I can light their way to the door.

Besides all these potential lights, I have lights on tall poles outside my house and my retreat house. These lights operate with a switch from inside the house, or with a device I can carry. I have to turn them on. When someone drives up, I can light their way to the door.

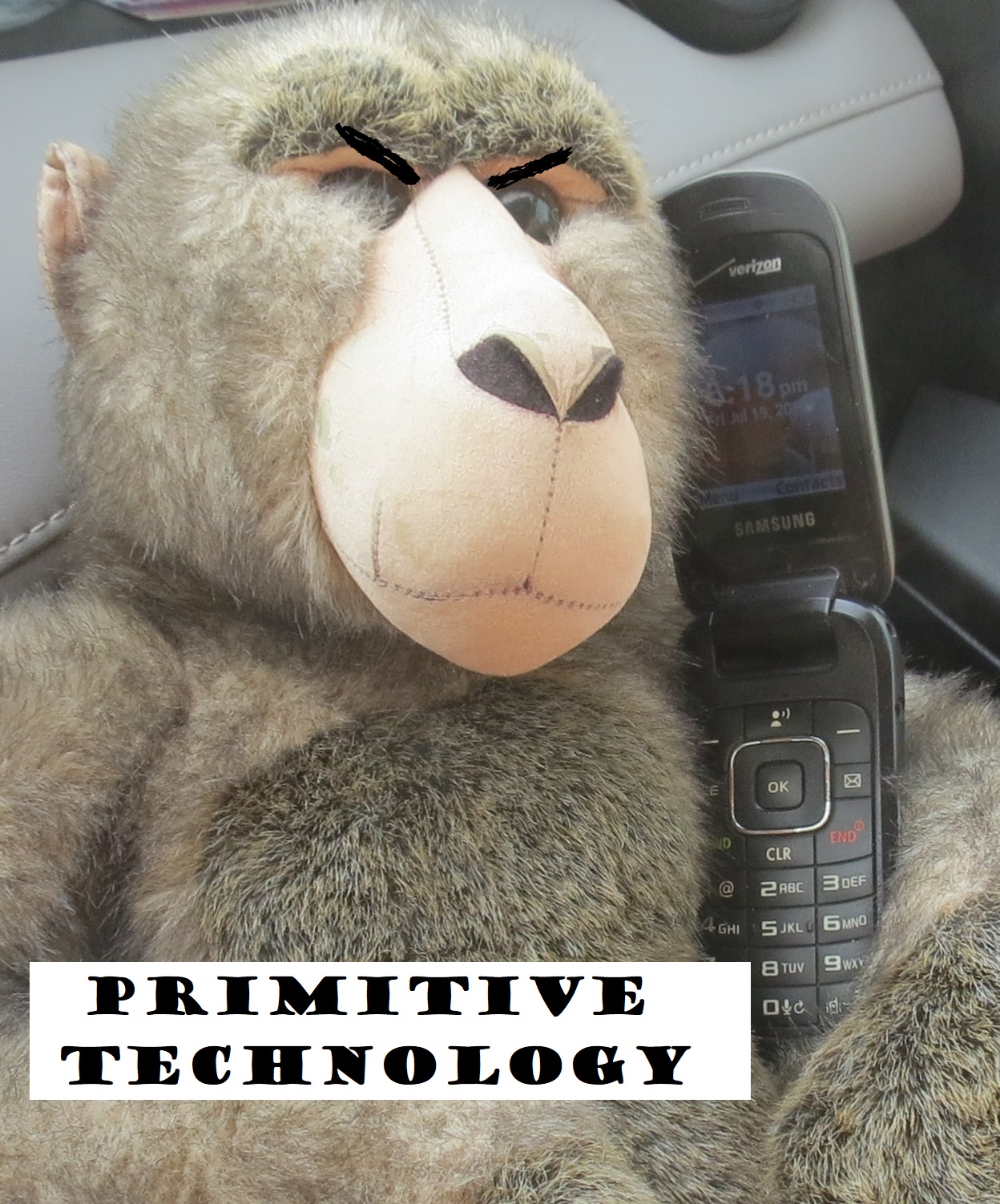

Now, when most people have phones with screens on them and multiple functions, I have an itty bitty cell phone that can’t be clamped to my ear unless my hand is holding it. I can’t type that way, so I can’t take notes. Therefore I use the cell phone to make calls at my most convenient time. I have a list of people who have this number so when they call I can, at a glance, decide if I must interrupt whatever I am doing to respond.

Now, when most people have phones with screens on them and multiple functions, I have an itty bitty cell phone that can’t be clamped to my ear unless my hand is holding it. I can’t type that way, so I can’t take notes. Therefore I use the cell phone to make calls at my most convenient time. I have a list of people who have this number so when they call I can, at a glance, decide if I must interrupt whatever I am doing to respond.

And please

And please I cursed and threatened revenge on the voles, but found no way acceptable to me. I don’t want to use poison, since it would kill more than the voles, so our best anti-vole devices are the two West Highland White Terriers. Unfortunately, they are more excitable than efficient, so they only catch one or two voles a week out of the thousands—or millions—living and tunneling under our feet.

I cursed and threatened revenge on the voles, but found no way acceptable to me. I don’t want to use poison, since it would kill more than the voles, so our best anti-vole devices are the two West Highland White Terriers. Unfortunately, they are more excitable than efficient, so they only catch one or two voles a week out of the thousands—or millions—living and tunneling under our feet. June brought heavy rains and flooding along the usually dry gullies. The redwinged blackbirds nest in groups along watercourses, weaving grasses and moss into a tight bowl tied to the surrounding cattails or willow bushes. Each nest is lined with mud, and may be as high as 14 feet above the water—or as low as three inches. I worried that the nests and chicks had been drowned, but didn’t want to slog into the deep mud and piles of debris to search. After a few days, the redwings seemed as busy as ever, but I didn’t know if they were feeding survivors or building new nests.

June brought heavy rains and flooding along the usually dry gullies. The redwinged blackbirds nest in groups along watercourses, weaving grasses and moss into a tight bowl tied to the surrounding cattails or willow bushes. Each nest is lined with mud, and may be as high as 14 feet above the water—or as low as three inches. I worried that the nests and chicks had been drowned, but didn’t want to slog into the deep mud and piles of debris to search. After a few days, the redwings seemed as busy as ever, but I didn’t know if they were feeding survivors or building new nests.

Both dogs will shove their heads inside a tire, and then move toward each other, trapping the rabbit between them. Eventually one of them is able to bite the rabbit, which squeals and excites the other dog into biting whatever he can reach. By the time we hear the shrieks, the dogs are yanking on the rabbit from opposite directions and we’re too late to save it. Nature’s policy in this case is cruel, so one of us finishes killing the bunny.

Both dogs will shove their heads inside a tire, and then move toward each other, trapping the rabbit between them. Eventually one of them is able to bite the rabbit, which squeals and excites the other dog into biting whatever he can reach. By the time we hear the shrieks, the dogs are yanking on the rabbit from opposite directions and we’re too late to save it. Nature’s policy in this case is cruel, so one of us finishes killing the bunny. But one day, when I heard the familiar commotion of blackbird calls, I looked up to see that the bird fleeing from them was a Great Blue Heron! The bird’s ponderous wings scooped air and its neck was folded back, but its size didn’t seem to deter the little birds who darted at it again and again until it disappeared.

But one day, when I heard the familiar commotion of blackbird calls, I looked up to see that the bird fleeing from them was a Great Blue Heron! The bird’s ponderous wings scooped air and its neck was folded back, but its size didn’t seem to deter the little birds who darted at it again and again until it disappeared.