In honor of National Cowboy Poetry Week (April 21-27, 2019), I am reprinting this blog, which was originally published July 30, 2012 on my website’s blog page.

++–++–++–++–++

Recently [July, 2012] I presented a workshop at the combined annual meeting of the Dakota Cowboy Poets Association and the Western Writers Group, held at Slim McNaught’s house in New Underwood, South Dakota.

My workshop was With the Net Down: Do You Dare to Write Without Rhyme? Briefly, I discussed the differences between rhymed, metered poetry and free verse. Poets like myself, who don’t generally use rhyme, often hear Robert Frost’s statement that writing poetry without rhyme is like playing tennis with the net down. Many rhyming poets think that free verse just means the poetry doesn’t rhyme.

In fact, rhyme or the lack of it has nothing to do with defining free verse.

Free verse can be rhymed or unrhymed but its primary characteristic is that it has no set meter.

No set meter. That’s not the same as having no meter at all.

Here’s a fine and familiar free verse poem:

Our Father, which art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy Name.

Thy Kingdom come.

Thy will be done in earth,

As it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive them that trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

The power, and the glory,

For ever and ever. Amen.

Free verse. And when one person or a congregation is repeating those words, you can hear the rhythm.

I don’t want to repeat here everything I had to say at my workshop, let alone everything there is to say, about meter. The set acoustic pattern of a line of poetry is its meter or rhythm and may be measured in syllables, accented syllables, or both. Thus meter is often defined by the number of syllables in the line.

Most of us speak in iambic: collections of one unaccented followed by one accented syllable:

I’m GO-ing TO the GROcery STORE to-DAY.

That’s iambic pentameter: five iambic (da-DUM) feet.

Because we speak in iambics, we appreciate poetry that uses them. Blank verse is usually unrhymed iambic pentameter: five pairs of iambs. William Shakespeare and John Milton both favored this form.

But other kinds of feet exist: Pyrrhic is two unaccented syllables: da-da; Spondee two accented syllables: DUM-DUM; Trochee an accented and an unaccented (DUM-da) and so forth. Free verse has meter but not usually meter as regular as the conventional rhymed iambic pentameter pattern of cowboy poetry.

My favorite articles about cowboy poetry, including information about unrhymed poetry, appear at www.CowboyPoetry.com, written by cowboy poet Rod Miller. If you write poetry, rhymed or otherwise, you ought to read these. [link posted below]

As Rod Miller says, any good free verse poem uses the kinds of literary tools and techniques that elevate all good poetry to a level above ordinary writing:

“. . . tonal quality, word choice, allusion, onomatopoeia, metaphor, layered meanings, imagery, and such like. The lack of discipline offered by the absence of meter and the opportunity to cast aside rhyme do not give a poet free rein to be less than poetic, any more than strict adherence to rhyme and meter allow a poet to use otherwise ordinary language in creating verse.”

Most of us don’t live up to the high standards set by the best writers. I’ve never heard a rhyming cowboy poet better than Wally McRae or a free verse cowboy poet better than Paul Zarzyski. And plenty of bad poetry of every type finds its way into print.

We all want the same thing: to tell our stories and have people listen to and enjoy them.

In my workshop, I challenged the assembled cowboy poets and their spouses to write about a subject without trying to rhyme. Several people produced drafts that could turn into good poems of one kind or another.

The question and answer session turned into the most fascinating discussion I’ve had on the subject of poetry in years.

During the workshop, I’d read a couple of Paul Zarzyski poems as illustrations of fine free verse poetry.

Cowboy Poet Robert Dennis of Red Owl, South Dakota, asked if all free verse poetry is meant to be read aloud.

Cowboy Poet Robert Dennis of Red Owl, South Dakota, asked if all free verse poetry is meant to be read aloud.

“Because,” he said, “listening to what you just read, my brain just can’t keep up. I realize those are interesting words and lines, but there’s so much happening in the poem that I lose the meaning.”

I could see instantly what he meant.

Here’s a bit of Paul Zarzyski’s poem “On my Birthday, The Serpent–” that I read during the workshop. (I’m reproducing it here without his specific permission because it appears on his website and I think he’d approve of my using it in a teaching context and Paul refuses to use email so gaining his permission by mailing a letter to ask him could take weeks.)

disturbed from his moist coiled sleep in the cool

humus beneath the horse trough

triveted an inch off the ground

by mildewed boards–glides

between my feet. It has been

startled by water

hose thrashing the roof

over its head, brass nozzle

striking side-to-side

wildly under the sudden thrust–spigot

handle yanked up full.

Though I’d practiced reading those first lines many times, I still muffed “moist coiled.” The rest of the words are so filled with imagery, tone, alliteration and layered meanings that I had to read the poem several times to try to get the full meaning into my reading. The vivid, complex language had grown more fascinating with each reading.

But could someone hearing the poem for the first time understand it? Only after I’d read it several times did I really appreciate many of the nuances.

“So can it be,” Robert persisted, “that some free verse poetry should be read on the page and not performed?”

“So can it be,” Robert persisted, “that some free verse poetry should be read on the page and not performed?”

That idea had never occurred to me but I think he’s right. Some poetry that I’d call excellent would be extremely hard to understand if you only heard it once. Only after many readings and thoughtful pondering can the reader grasp the meaning.

Should such poetry be read aloud? Probably not if the poet’s primary aim is to be understood. Audiences who listen to Zarzyski, though they may not understand the entire meaning of a poem, are thoroughly entertained by the explosive, dynamic presentation.

Poetry is far older than writing. No one can be sure precisely where the art began but it probably arose as spells spoken or chanted in early societies to promote harmony and good harvests. Ancient societies such as those in Greece and Rome made poetry part of religious rites. Later it became the way to transmit and recall the stories of a civilization’s struggles and victories. Traveling troubadours in later societies were often singing or reciting news events; rhyme and meter helped everyone remember the stories.

So the cowboy poet who recites stories of his daily life is considerably closer to the true origins of this ancient art than the academician who lards his lines with italicized words and loads on footnotes to explain all the references.

When I mentioned my discussion with Robert to publisher Nancy Curtis [High Plains Press, Glendo, Wyoming], she added another element.

Some poetry that sounds terrific when read or recited aloud is not well written; the images may be cliched or the rhythm rough. Part of the magic lies in the poet’s performance. Poets who regularly entertain audiences may be more interested in making the story entertaining than in making it conform to any “rules” of poetry.

Meanwhile, some poetry that is technically excellent isn’t enjoyable to listen to or is too complex to reveal its meaning when read or recited aloud. A solitary reader might appreciate the meaning but an audience just doesn’t have time during one hearing.

Logically, then, the poetry that has the best chance of resounding in the minds of audience members is that with strong rhythm and rhyme: those familiar elements that allow the audience to become part of the story. This is one reason cowboy poetry has become so popular.

Conversely, free verse poets who plan to recite their work before audiences should consider whether or not their work can be understood when recited. Rather than simply distributing gorgeous language and long lines across the page, we free verse poets need to spend more time studying those many methods of using meter in order to create poetry rhythmic enough to satisfy the audience’s love of regularity and make memorable lines.

Robert said in a later conversation, “I do enjoy the good stuff,” just as he enjoys the best rhymed poetry. And sometimes as he works on a poem, he added, he gets “caught up in the rush to share it before it’s at its best. Kind of like showing off your new baby instead of your college graduate!”

And perhaps we need to relax and allow poetry created to be performed to be judged by a different standard than poetry created for deeper study. I am not ready to trade flamboyant cowboy performers for fellows in three-piece suits reading footnoted masterpieces of obfuscation.

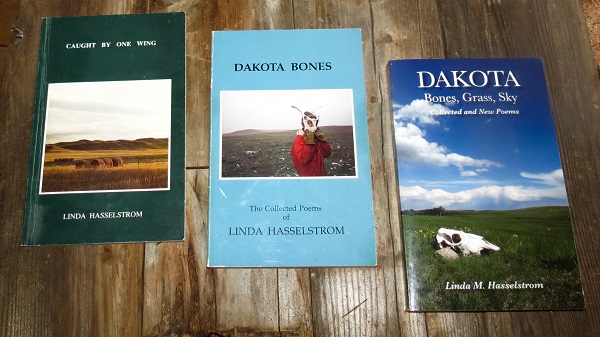

Linda M. Hasselstrom

Windbreak House Writing Retreats

Hermosa, South Dakota

© 2012 and 2019, Linda M. Hasselstrom

# # #

If you are at all interested in Cowboy Poetry, the website to visit is www.CowboyPoetry.com where you will find poems, blogs, history, stories, cds to purchase, and current events all relating to western poetry, new and old, rhymed and not– including webpages about the poetry of Slim McNaught, Paul Zarzyski, Robert Dennis, Rod Miller, Wally McRae, and Linda M. Hasselstrom (and many more).

This poster from CowboyPoetry.com celebrating Cowboy Poetry Week, features art by Shawn Cameron. Find more of her western art at her website www.ShawnCameron.com

The essays by Rod Miller about Cowboy Poetry, mentioned in my blog, may be found on the CowboyPoetry.com website by clicking here.

“That’s one of many stories inspired by local history, with the names changed to protect the — guilty. And yes, “Homesteading in Dakota” is taken straight from one of the stories my father told me, with tight lips and in terse sentences, once when we were moving cattle near where the homestead stood. I believe he immediately regretted telling me, but once a writer has a story in her head, it may lodge and grow there.

“That’s one of many stories inspired by local history, with the names changed to protect the — guilty. And yes, “Homesteading in Dakota” is taken straight from one of the stories my father told me, with tight lips and in terse sentences, once when we were moving cattle near where the homestead stood. I believe he immediately regretted telling me, but once a writer has a story in her head, it may lodge and grow there.

One of the easiest ways to begin a poem is by describing an action or an event. This is another reason to keep a journal: many of my poems begin as notes in my journal, simply so I don’t forget a particular incident. Sometimes I immediately believe the notes might become a poem, and begin writing a draft right then, often on the computer. Just as often, however, I am simply recording the information, and only later do I begin to consider it as poetic material.

One of the easiest ways to begin a poem is by describing an action or an event. This is another reason to keep a journal: many of my poems begin as notes in my journal, simply so I don’t forget a particular incident. Sometimes I immediately believe the notes might become a poem, and begin writing a draft right then, often on the computer. Just as often, however, I am simply recording the information, and only later do I begin to consider it as poetic material.

After this point, though, the poem took over the writing, and it was no longer strictly fact. I no longer remember how long this process took, but no doubt several revisions as I considered the poem, both consciously and unconsciously.

After this point, though, the poem took over the writing, and it was no longer strictly fact. I no longer remember how long this process took, but no doubt several revisions as I considered the poem, both consciously and unconsciously. Instead, memories of several of my aunts intruded: they were always patching jeans. And an aunt who will remain nameless here had at least three freezers in her basement full of preserved garden produce. The same aunt once took me to the cellar where rough wood shelves held hundreds of canning jars, some of which were so ancient that the contents couldn’t really be identified. After she died, we hauled them all to the dump.

Instead, memories of several of my aunts intruded: they were always patching jeans. And an aunt who will remain nameless here had at least three freezers in her basement full of preserved garden produce. The same aunt once took me to the cellar where rough wood shelves held hundreds of canning jars, some of which were so ancient that the contents couldn’t really be identified. After she died, we hauled them all to the dump. My comp copy of Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness & Connection arrived yesterday, and I’ve gotten behind on the news (thank goodness!) because I keep picking it up to read another fine poem.

My comp copy of Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness & Connection arrived yesterday, and I’ve gotten behind on the news (thank goodness!) because I keep picking it up to read another fine poem.

To improve the experience, I took my notebook outside to write each day’s verse. So when I wrote on Sunday about the sun feeling hot on my face, I was sitting in a green plastic chair against the wall of the garage, facing west as the sun dropped toward the Black Hills. Three red-winged blackbirds were singing from three cedar trees in the shelterbelt on my left, south of the house.

To improve the experience, I took my notebook outside to write each day’s verse. So when I wrote on Sunday about the sun feeling hot on my face, I was sitting in a green plastic chair against the wall of the garage, facing west as the sun dropped toward the Black Hills. Three red-winged blackbirds were singing from three cedar trees in the shelterbelt on my left, south of the house.

Cowboy Poet Robert Dennis of Red Owl, South Dakota, asked if all free verse poetry is meant to be read aloud.

Cowboy Poet Robert Dennis of Red Owl, South Dakota, asked if all free verse poetry is meant to be read aloud. “So can it be,” Robert persisted, “that some free verse poetry should be read on the page and not performed?”

“So can it be,” Robert persisted, “that some free verse poetry should be read on the page and not performed?”

This has been a busy week; I read and commented on a 140-page manuscript, planned three retreats, made 6 pots of tomato sauce, worked on a home page message, and read six mystery books as well as the usual three meals a day, watering the garden, writing a few letters and no doubt a few chores I’ve forgotten. Sometimes it seems as though the world keeps spinning faster and faster.

This has been a busy week; I read and commented on a 140-page manuscript, planned three retreats, made 6 pots of tomato sauce, worked on a home page message, and read six mystery books as well as the usual three meals a day, watering the garden, writing a few letters and no doubt a few chores I’ve forgotten. Sometimes it seems as though the world keeps spinning faster and faster. In creating the bouquet, I create a little island of calm in the middle of hurry. And every time I look at it, I recall choosing it, and I also take a moment to enjoy its uniqueness. Each one lasts only a few days, but each provides considerable balm. Once the flowers have finished blooming, I often make a little bouquet from dried weeds and leaves, with the same effect.

In creating the bouquet, I create a little island of calm in the middle of hurry. And every time I look at it, I recall choosing it, and I also take a moment to enjoy its uniqueness. Each one lasts only a few days, but each provides considerable balm. Once the flowers have finished blooming, I often make a little bouquet from dried weeds and leaves, with the same effect. noises are quiet; I can hear nothing but the wind through the grass, perhaps the light tinkle of a wind chime from the deck.

noises are quiet; I can hear nothing but the wind through the grass, perhaps the light tinkle of a wind chime from the deck.