The July/August issue of Poets & Writers, one of the best resources for writers I know, features an intriguing article, “Secrets Hidden in the Stacks” that is going to send me prowling through my local library.

The story concerns a University of Virginia professor who sent his class to the library to look at 19th century copies of work by a sentimental poet of the time, Felicia Hemans. What the students found was not just the books, but a wealth of information added to them by readers. Diary entries, quotes, pressed flowers and the readers’ attempts at poetry were scribbled in the margins or tucked inside the books.

The professor, Andrew Stauffer, was so fascinated by the additional history furnished by these oddments that in 2014 he founded the Book Traces project (booktraces.org) to investigate what else might be hiding in the library. He invites anyone to submit photographs of the “traces” they find in library books published before 1923– meaning books that are in the public domain– in circulating collections.

With a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources, he hired assistants to search thousands of books on the open shelves of UVA’s libraries and catalogue the information: “a collection within the collection.”

The project expanded, and today extends to schools from Arizona State University and Bryn Mawr College, and has documented more than 3000 such traces. One of his favorite finds was doll clothes pressed into an 1833 copy of a book by Sir Walter Scott. The photo furnishes the cover of the resulting book: Book Traces: Nineteenth Century Readers and the Future of the Library.

“We’re fighting against the idea that once you’ve digitized a single copy, then you don’t need others, says the professor.

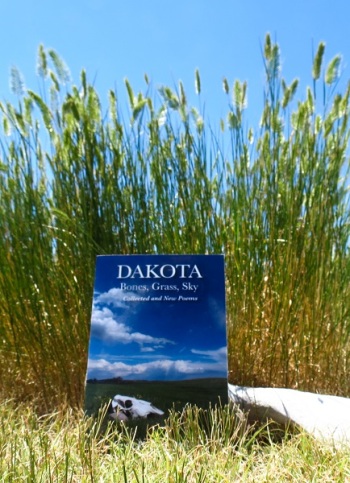

On the day that I read this article, I received a call from poet Wally McRae, the reigning king of Cowboy Poetry. I’d sent him a copy of my collection Dakota: Bones, Grass, Sky, published by Spoon River Poetry Press in 2017. I didn’t ask or expect a review from Wally. Still, I thought he might enjoy or be inspired by some of the poems, especially since Wally believes all poetry should rhyme, and most of mine do not.

On the day that I read this article, I received a call from poet Wally McRae, the reigning king of Cowboy Poetry. I’d sent him a copy of my collection Dakota: Bones, Grass, Sky, published by Spoon River Poetry Press in 2017. I didn’t ask or expect a review from Wally. Still, I thought he might enjoy or be inspired by some of the poems, especially since Wally believes all poetry should rhyme, and most of mine do not.

And I thought that someday, when this virus is not the primary fact of daily life, we might have a conversation about poetry.

Wally called a couple of days ago, and I was delighted to learn that he has not only been reading Dakota, he’s been having a conversation with me in its pages: writing comments and questions as he reads!

“I am not a good judge of free verse,” he said. His favorite poem in the book is “Mulch”– a surprise to me. He liked the line “You will not find naked soil in the wilderness,” and he enjoyed knowing that when I mulched with magazines, “Robert Redford stared up/ between the rhubarb and the lettuce.”

His favorite poem in the bunch, though, was “Learning About Gates,” which led to him telling me about an alcoholic handyman who once worked for his father, and built gates that are still legendary throughout the county.

I could hear him turning pages as he spoke, and soon he mentioned more poems he liked: “Handbook to Ranching,” another poem dedicated to my father, beginning with one of his strongest rules: “Don’t spend any money.”

I could hear him turning pages as he spoke, and soon he mentioned more poems he liked: “Handbook to Ranching,” another poem dedicated to my father, beginning with one of his strongest rules: “Don’t spend any money.”

Another poem about fences, “Apologies to Frost’s Neighbor” likewise pleased him, and “Milliron Ranch” reminded him of a homesteading story from his own neighborhood.

Wally laughed at himself for admitting to me that he was scribbling in the book, but he wanted to remember things to say to me. He understood why “there are a lot of driving poems in the book,” since Westerners have to drive long distances to practically everywhere, and chuckled at “Speed Warning,” dedicated with gratitude to the Highway Patrolman who stopped me on one drive to the ranch from Cheyenne, and may have saved my life– or at least the life of an unwary antelope.

So that book of poetry has already fulfilled my highest hopes for it: As he read, Wally enjoyed, debated, questioned, and was stimulated by the words of another writer, recognizing the real voices of people he might have known in the words of the poet.

And on some future day, another reader may discover Wally’s notes and comments in the book and continue the conversation, and the inspiration, without ever having known either of us.

Look for secrets in book– in several ways.

(And please– write only in the books you OWN– some day they may make their way to a library; but please don’t write in library books.)

Linda M. Hasselstrom

Windbreak House Writing Retreats

Hermosa, South Dakota

© 2020, Linda M. Hasselstrom

# # #